The Death of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (pictured above) captures the moment Socrates, embodying logos as self-aware reason, chooses philosophy (the self-examined life) and the grasping of inner necessity over external justification and dogma.

Intro

World consciousness has achieved a distinct stage of development characterized by a specific capacity. Previously, earlier stages found consciousness more embedded in bodily sensations, habits, and communal and traditional feelings. Now we find that the individual, having individuated, has developed a new capacity to turn awareness back upon itself. The Ancient Greeks identified this capacity with the term Logos. Logos signifies the principle of order and self-aware intelligence that distinguishes human nature. It is the power that allows us to step out of an immediate being and say “I” to ourselves. The activity of this being which allows us to distinguish ourselves is found in the dictum, “I exist because thinking distinguishes me from everything else”. Here, thinking establishes the self as a distinct entity, separate from the undifferentiated totality of the world. Logos is this activity of self-recognition that sets us apart and yet connects us to the rational structure of the cosmos. What this means for the individual, is that the individual person no longer receives experiences from the world, or even their own inner life. They can hold their own conscious processes at a distance while examining them, coming to recognize them as distinct activities. The telltale sign of this stage is a detachment from immersion; the individual has the ability to separate themselves from the immediate flow of experiences, feelings, and even thoughts, to see them as objects of contemplation. As a result, the individual sheds the immediate identity of itself with its experiences, opting to become aware of itself as an experiencer. A strong sense of responsibility for one’s own selfhood emerges. This responsibility is unified with the search for knowledge, particularly with the drive to understand the world and the self through principles, reasons, and truths that the individual can verify themselves internally. It may be permissible to repeat oneself in certain cases, and I’m surely not one who will pass off an opportunity to advertise themselves. So, I will take this time to reference my previous writings on this stage and its appearance in the history of man:

Socrates is important here, since now that knowledge is not revealed through omens and oracles, it becomes elicited through subjectivity. Marked by the emergence of the Socratic method, where the subject looks outwards towards other subjects to see the correspondence between what is said and the internal coherence found within the ego, and the logical deduction of Aristotle (seen through the syllogism), what you find isn’t a total departure from reality. Instead, this moment serves as a translation of totality into conceptual form, where consciousness needs to grasp the relationship between the internal subjective act of thought, to “being”. In other words, the spirit descends into full self-conscious individuality, but at the cost of the split between the subject and object in its philosophic form, the form relevant for this age of consciousness/intelligibility. For the first time, man stood clearly as a thinking subject over against a world of objects to be known. Socrates asks “what is the good life” rather than asking “what do the Gods will?”. Plato asks, “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?”. Answers to these questions are then sought within human reason because they cannot be answered in a way which generates inward necessity with myths and stories. And so, Plato’s Forms are intelligible to us as this new layer of man grasping the spiritual world in the mode of thought, rather than image or myth. What was once known as the Egyptian God Ma’at (cosmic order/truth) has turned into Plato’s Form of Justice, the abstract ideal discovered by mind.

Within this stage of reflective awareness, thinking (particularly in its matured, conceptual form), emerges as the defining central activity in distinction to the associative, dream-like thinking of earlier states. It is the disciplined activity of forming concepts, judgments, and ideas. Of all our inner activities - feel, willing, sensing, etc. - thinking is the only one we can observe while at the same time being its active agent. We feel inside our feelings, and we are carried along by our will, but we can consciously direct and watch ourselves think. This makes thinking the most immediate and transparent process for the newly awakened self-reflective faculty. It is the first activity where the “I” can clearly catch itself in the act. This activity of thinking is characteristic of our current “stage” for this reason. In doing so, the goal is to overcome vague, subjective impressions. Thinking, by its nature, works with concepts like “triangle”, “justice”, and “cause”, that are the same for any reflecting mind, making these concepts universal. Hence, it represents a move away from the private, subjective world of feeling, towards a shareable, objective world of meaning. Additionally, the clarity and lawfulness of thought itself echoes this stage’s desire for a foundation beyond personal bias, having established the individual and individual thought as parsing intelligibility (and hence not putting personal bias in distinction with external truth). The very act of achieving self-reflective awareness creates an inner split. The observing “I” is put face to face with the experienced content (this may be the world, the body, or various experiential content like feelings). Thinking is uniquely the faculty which can can bridge this split between the subject and object. By thinking about my feelings, I understand them; by thinking about the world, I connect myself to it conceptually. Thought is the active power that seeks to heal this division. It is the seat of autonomous freedom, experienced as a self-initiated, self-guided activity. I follow the consent of my concepts, not a physical compulsion (and in the future, these processes, and faculties will be unified in such a way that it will cause a physical compulsion. What a world to live in, where an objective measure of justice is arrived at, and man is physically compelled to realize it). When one thinks, they are not reacting. They are actively brining forth connections from within themselves, and therefore, the experience of thinking becomes the primary inner model and foundation for what freedom feels like.

The quest for true freedom in philosophy has often been framed as the project of self-determination, or the capacity of a thing to act from the essential nature of its own being, as opposed to being externally determined. Truly, any free thing can be called self-determining, and any self-determining, free. Our exploration of thought, and it’s destiny, for it to be genuinely an exploration of thinking, must approach thought on its own terms as a self-determined activity. If we begin by assuming thought is a byproduct or an effect of something else (such as matter in motion), we have already ceased to examine thinking as thinking. We will have substituted it with a different object of study: the physiological conditions that may accompany it. In order to understand the essence of thought, we must attend to what thinking itself reveals as an activity that follows the inner necessity of Ideas. Thinking is not causally linked to biology and neurons in the way that a physical effect is linked to its cause. Matter, as observed by the senses, and studied by physics, operates under different “laws” than thought. When I reason from a premise to a conclusion, the connection is made by the ideal content of the concepts themselves, not by an electric spark in my brain. As Rudolf Steiner observes, “Nothing is present for me by which to guide myself except the content of my thoughts; I do not guide myself by the material occurrences in my brain”. The claim that consciousness or thought are downstream from matter, is to establish that the correlation between certain patterns of neural activity and certain states of conscious thought is a causal relationship. But correlation is not causation. The consistent accompaniment of A (neural firing) and B (thought) does not prove that A generates B, since there is no necessary connection. It remains just as valid a hypothesis that B (a self-determined thinking activity) organizes or expresses itself through A, or that both A and B are two manifestations of something deeper and ideal. To assert the primacy of matter is a dogmatic assumption which finds no backing from logic, reason, or truth. Therefore, to give the phenomenon of thinking its due, we must treat thinking as it is. This means studying it first as a self-contained spiritual activity which we experience. An activity that connects ideas according to their own meaning and necessity.

This activity of thinking reveals itself as what accords to the inner necessity of Ideas and Concepts. In thinking, we follow the connections inherent in the content of our thoughts. It is this very self-determination which distinguishes subject from object. An object is determined from without, a subject determines itself from within. The placing of this self-determination (of the “I”) finds its being in thinking. Within this activity, thought actively forms concepts and judgments, and grasps Ideas. Concept, to define properly, is the unifying principle that brings coherence to a manifold of sense impressions. For example, the concept “tree” is not abstracted from many individual trees, it is the ideal archetype that allows us to recognize any particular tree as such. Similarly, an idea is a higher more encompassing concept, it is totality, or in other words, a spiritual reality that thinking can intuitively grasp (return to this sentence when the phrase “intuitive thinking” becomes less foreign). The word “concept” itself, from Latin concipere, to “conceive”, reveals this generative power. Thinking conceives, gives birth to, the object in its ideal form. Thus, the Idea is a spiritual being. It is a living, active principle that thinking engages. It is through Concepts and Ideas that the raw material of perception is structured into a meaningful, unified whole. Thought is the activity of achieving this unity, bringing the ideal into relationship with and making sense of the perceptually given. For more focus on what is called the “Ideal”, a short read is provided here.

Observing Thinking versus Thinking Thinking

In the ordinary course of conscious life, when we think, our attention is usually directed entirely toward the object of thought. Whether we are reflecting on a math problem, or planning our day out, the content occupies the foreground. We think about things, while the process of thinking itself remains transparent and unnoticed. The reason for this is that thinking is not one object among others. It is the very activity by which we engage objects. We don’t, in the moment of thinking, watch ourselves think. The reason being, the two activities, as the active production of thought and contemplative observation of them, cannot happen at the same time. This would be like a derivative of thinking - thinking of something, and thinking of that process. It is comparable to an artist fully immersing themselves in a painting, while critically observing each brushstroke. Likewise, we can only observe our thinking in retrospect. If we want to observe ourselves thinking, we need to step back and turn our attention to the spiritual activity itself. By successfully observing thinking, we direct our attention to the activity.

Note: Mentioned is thinking. Including the capacities of feeling and willing would be seem unjustified, but it is worth noting that thinking is in a relationship with feeling and willing. In the act of thinking, we experience a feeling of evidence, or of correctness, when our thoughts align with their object. This feeling is not the truth itself, but it signals a telos, or an orientation towards truth, and a drive for alignment with being. Feeling in thinking is an inner compass that guides us towards adequacy and intelligibility. Thinking is also filled with will insofar as it is the deed of Spirit, and it is the deed of the subject. Thinking requires effort and intention. One can choose to consciously think about things, which shows a voluntary direction. Although, as mentioned before, most people think about things unconsciously. However, one can also willfully choose to engage in a conscious negation of thinking. Look to mindful meditation as an example.

When philosophers like Aristotle describe a self-contained “thinking of thinking” (noesis noeseos), or Georg W. F. Hegel who has one follow along with what thinking produces by thinking alongside thought, they engage in a process of logical reflection upon the finished forms of thought. They take the results of thinking as it thinks itself, like concepts, judgments, syllogisms, and logical laws, and make these results themselves the new objects of a further act of thinking. There is, at present, a meta-level analysis. Aristotle analyzes categories and the forms of reasoning which constitute valid thought. Hegel’s Science of Logic traces the necessary result of the Concept through its own immanence and emergence in thought. In both cases, “thinking about thinking” means applying thinking to its own products. The activity of thinking recedes into the background. What is really examined is a scaffolding of thought, a series of logical relations. This method treats thinking as a completed object to be dissected by a higher-order thought, perpetuating the very subject-object split such methods claim to overcome.

Hegel is the figure most characteristic of this age of consciousness. He correctly identifies thinking as what elevates the soul to spirit. Steiner himself cites Hegel in the Philosophy of Freedom, saying “Only with thinking does the soul, with which the animal is also endowed, first become spirit”. Hegel’s core claim can be said to be that the self-movement of the Concept is the true path to knowledge, overcoming the subject-object divide and providing true knowledge. For Hegel, in the act of thinking, thinking and being are one. Spirit thinks itself. However, there is a silent perceptual act ignored in the schema. The thinking itself is done by a subject, and this subject is implicit! The embodied act of thinking by the subject is left implicit; the subject is left suspended until subjecthood immanently proves itself to be the one thinking. The problem is, methodologically the system ascribes to subjecthood, the incarnation of one unified Concept. True subjecthood is never arrived at, and as such, the freedom attained by the subject in this schema is one of servitude. Thought in Hegel’s schema is neither fully subject nor reaching object, merely describing the logic of these things. In other words, Hegel’s method produces one unified logical organism called the Concept, a totality which generates all meaning through itself. The “subject” (subject is in quotations, because true subjecthood has not been established) in this case is left with two options. Either align yourself with this organism (which implies a comprehension of this logical organism as constituting your own), or reject it entirely, which leads to non-being. This is essentially servitude, an alienated consciousness which does not know itself coming to the Concept, and the Concept saying to it “it’s my way or the highway”. Essentially, this is one of the reasons Steiner accuses Hegel of logicism, of fetishizing logic. The response from the Absolute Idealist perspective will present this accusation with the following:

The fact that the individual’s act of thinking is the local manifestation of the global act of thought, that it is the self-actualizing movement of Spirit, is the fundamental truth. The philosophical system is the journey where consciousness, or the subject, realizes this. The individual’s very existence as a rational being is Spirit aligning with itself. Likewise, what is called servitude or slavery here is in actually freedom as the recognition of necessity. This is substantial freedom, the necessary outline by which freedom can come to recognize itself. The act of interfacing with this substantiality is true freedom, that this activity, after being objectified in the world, is accepted and comprehended as the subject’s own. The description is essentially true (as you will find with all of Hegel’s logical exposition), but the evaluation is wrong. There is a turn yet to be recognized. This turn is the full exposition of the “local” function of thought, an establishment of the subject’s activity. Through the observation of thinking, one makes a discovery that within experience, the thinking activity, though performed by the individual, follows universal, ideal laws. Through this method, the “I” recognizes itself as a site where universal ideality becomes actual. The “I” realizes starting from the subject that subjective thinking is the substance of the thinking subject itself. This connection between the “local” function of thought, and the “global” will be explored later.

Let us look at it from another position. Let us grant that the thinking activity of the subject is established as truly belonging to the subject, that the activity being done is magically drawn out from its implicit shell by the subject, into explicit view in the act of “thinking about thinking”. Although this would be counter to the system’s identification of thought as universal manifesting in the individual, let us grant the starting point that the subject is engaging in what Hegel would call “absolute knowledge”, bridging the subject with the object. This is for the purpose of demonstrating the issue with the logical organism known as the Concept. Imagine the subject’s power of thought as an expanding balloon-like membrane, that, through systematic thought, grows to cover the entire world as the system finds its completion. The outlines of the objects by this membrane are correct, shaped by the being of what they cover. Insofar as the subjective act is structurally true, it will find its correlate in the world. But the “thinking” of the objects are not themselves sourced from the objects. There is no true establishment of knowledge of the object itself, only its logical impression. Moreover, there is no true separation of objects, as the balloon-like membrane is one continuous surface. The “Concept” becomes a blanket that covers everything, but does not penetrate to the unique reality, or spiritual being, of each thing. What one would find is that the subject creates a world which is inaccessible to it. The “Concept” truly lives up to its name, since it is what births (hence conception) all knowledge in this system, and likewise, is marked and mediated by it.

It would be misleading to say that Hegel makes an error, since, all he is doing is adhering to the standard of thought as it thinks itself. But it would be just as misleading to not point out what results from the method. The result is that every mode of knowledge is either reduced to a stepping stone in the immanent development of thought, or disregarded as misguided or confused. This applies even to experiences which resist immediate conceptualization. Alien encounters, Christic visions such as in the case of John of Patmos in Revelation, or parapsychological phenomena (such as remote viewing and what is called astral projection) present content for which one cannot think the generative reality. The Absolute Idealist would try to extract an ideal truth from the report, but this would not do justice to the experience itself, nor would it be extracting truth, instead locating the correlative Concept and picking and choosing which aspects align most with the logical exposition. This is not hearsay- Hegel’s system already has a place for parapsychological phenomena, classifying them as lower forms. He places experiences like “magnetism” and “somnambulism” (and by analogy all other extrasensory perception) in the section on Anthropology, before “self-feeling”. Reason and thinking judges them as yielding private, irrational content, and sees them as unfree lower forms of Spirit. In other words, there is no legitimacy in Hegel’s system of totality, for angels guiding your decision-making in order to save you. Had you done something differently one day which would have resulted in your death or injury, but, for example, received a dream or vision dissuading you, there is no room in the system to take this percept as it truly is. Fichte holds a similar view, naming the merely sensuous man as in a kind of waking somnambulism, or a slave to natural immediacy. These are ultimately inferior forms of knowledge, and subsequently freedom, seen at best as stepping stones. Hegel’s interest in parapsychological phenomenon reaches only insofar as these phenomena are empirical hints of a philosophical truth. One must ask themselves, to what extent can “Absolute Idealism” integrate perception, and what is the status of the subject?

Perception

The Persistence of Memory, by Salvador Dali

Perception is ultimately any given content of consciousness. For Rudolf Steiner, the term perception (Wahrnehmung, Steiner introduces the term “percept” in English) includes much more than its conventional philosophic and scientific usage. It’s not limited to the passive reception of external sense data like colors, sounds, and tactile qualities. Rather, perception designates any concrete content that presents itself to awareness before it is actively worked upon and interpreted by thinking. It is the raw, immediate “given” in any realm of experience. He states:

“I will call the immediate objects of sensation enumerated above perceptions, insofar as the conscious subject takes cognizance of them through observation… An emotion within myself can certainly be called a perception, but not a sensation in the physiological sense. I come to know even my emotions through their becoming perceptions for me. And the way we come to know our thinking through observation is such, that we can also use the word perception for thinking as it first appears to our consciousness.”

—(GA 4, p. 62)

Inner experiences are to be referred to as perceptions, since they do not constitute knowledge, only the immediate being of reality. Steiner consciously broadens the term to avoid artificial restrictions. The full scope of perception includes outer sense data such as the traditional objects of perception (colors, tones, temperature, etc.), inner feelings like states of pleasure, pain, mood, and emotional tone, mental pictures (Vorstellungen) such as dreams, memories, fantasies, and imagined scenes, spiritual impressions (by logical extension, any intuitive or spiritual content that initially presents itself to consciousness in a form not yet fully conceptualized would also belong to this category of the “given”), and finally, the phenomenon of thinking itself. When we reflect on our own thought-activity, that activity initially appears to our reflective gaze as a perception, or something we find ourselves doing or having. In other words, a given. Perception for Steiner represents one half of a complete reality. It is the particular, contingent, and manifesting side. By itself, the percept is unfinished; it is reality presenting itself in a specific, isolated form. A mere aggregate of perceptions would result in a world of disconnected fragments and immediacies, which disappear as soon as they appear. Perception then can be considered the what that is encountered, or as the question posed to consciousness. The developmental stage we are in is marked by its powerful capacity to grasp clear concepts and universal ideas. Its characteristic pitfall, however, is to misunderstand the ontological status of perceptions. It subjectivizes them completely, viewing them as private “mental pictures” or subjective representations caused by an external world, rather than recognizing them as the other essential half of reality itself and belonging to the object, intrinsic to knowledge about it. This error leads to two dominant, albeit one-sided, worldviews. The first is materialism and naturalism, which takes perceptions (especially sense data, since we live in times which denies ideality or a spiritual realm) as the sole reality, and reduces concepts to secondary, subjective byproducts or illusions. Here, only the perceptual pole is considered real. The other polarity is Abstract Idealism/Solipsism, which takes the conceptual world as the sole reality, and dismisses perceptions as mere illusory appearances within consciousness. Here, only the conceptual pole is considered real. Truth, full reality, or being, only arises in the active unity of percept and concept, or of observation (passive, not belonging to the subject) and thinking (the activity of the subject). The concept, or Idea, is the necessary counterpart to the percept, that provides its lawfulness, context, and meaning. Thinking’s activity is to seek and bring forth the concept that corresponds to the perception. A perception without a concept is unintelligible, and a concept without perception is empty. The task of knowing is to perform this unification, thereby healing the split between the self and the world.

Observation of Thinking Justified

Thought has a unique nature, since it is the only activity where the observer and the observed are identical within the activity. Unlike all other experiences where we stand over against an object (like a pencil, or a memory), in thinking, we are the activity we wish to know. Therefore, to know thought, we must perform an act of self-referential attention. We must, while thinking, turn our attention back upon the thinking itself. This creates a moment where the activity perceives its own activity. The only way to understand a self-determined activity is to experience its self-determination from within. Any method that treats thinking only as a finished logical product, misses the generative activity entirely. We may revisit the issue with the method of Hegel. While achieving a formal logical unity of subject and object, the act of the philosopher performing this thinking remains unexamined and never truly established. The system cannot describe itself as anything other than logical moment. Even when describing the unity of thought and being, the conscious subject is a blind spot. So, as opposed to “thinking of thinking”, we must engage in the observation of thinking in order to bring the subject into the light of consciousness, by addressing the question of who is thinking the system. In effect, we must turn from the content of thought (what thought generates), to the activity of thinking. In doing so, we achieve what Hegel’s system logically necessitates but cannot perform; we make the subject’s constitutive act its own witnessed object. This is the real moment of consciousness in the Consciousness Soul. It is the moment where conscious experience realizes that it is the active source of thought as a concrete contemplation of thought. One does not think “about” thinking in general, one attentively experiences their own thinking in action. This yields true self-knowledge in that you encounter the active spiritual essence of your own “I” as the performing agent. Furthermore, it provides the basis for world knowledge. In observing thinking, you experience a spiritual activity that is self-produced, yet universally valid (which will be explained in the next section). This self-produced activity becomes the known “organ” for investigating all other reality.

So far, an exposition of thought, and the necessary move to explain thought has been established. Thereby, a distinction between “thinking about thinking”, and “observing” thought has been made. Absolute Idealism would hear this distinction and interject with an accusation: “This is a regression to naive immediacy and subjective psychology. You have turned away from the pure self-mediation of the objective Concept to stare at your own private, contingent mental processes. This ‘observation’ is merely a form of sense-certainty applied inwardly. It cannot yield philosophical necessity, only psychological descriptions”. The key thing missing in this accusation is that it misunderstands the object of observation. We would not be observing the psychological processes (like the images, associations, and personal feelings), but the pure activity of forming ideational content. When I observe myself thinking through a mathematical proof, the content is universal. The activity producing it is my own, and I recognize it as my own, yet it is guided by logical necessity. What the Idealist thinker does not realize is that they themselves use this same self-produced ideally guided activity to construct the logical system, but foregoes the subject for the universal subject, the concept. This Concept is what we are abstractly, and are not afforded true individuality as persons whose thinking activity is our own. The thought of the Absolute Idealist is absolute, and “global”, and for that reason it will remain alienated. On the other hand, this approach of observing thought actually grounds the Concept in the conscious activity from which it is born. What is called the “pure self-mediation of the Concept” is an abstraction from the reality of thought as a living and embodied process that mediates concepts. Thus, the ultimate justification of the “observation of thinking” in contrast to the “thinking of thinking” is that it fulfills the implicit demand of Hegel’s own project. It achieves a knowing that is fully self-aware, and self-grounded, by closing a kind of performative gap.

Note: There is another accusation of “reflection” thinking which has been levied from Absolute Idealists, one that simply does not apply here. Steiner’s method of “reflection” constitutes an immediate self-observation of thinking as the activity itself. This stands in direct contrast to Hegel’s critique of reflection (Reflexion), which he condemns as an external and ultimately divisive intellectual operation that forever chases its own tail, positing a subject separate from an object. For Steiner, reflection is not an external analytical gaze upon finished thoughts. The term reflection interpreted this way carries the bias of the alienated Consciousness Soul. It is actually the internal turning of attention that experiences thinking’s own active presence from within, in this context. Ordinary reflection cannot split ourselves to observe the observing in the very instant it occurs. Steiner’s method accepts this by not attempting to “contemplate contemplation” as a second-order object. It opts for letting the activity of thought occur, then redirecting attention to the just-experienced activity itself, not as a new content, but as a realization of the process as belonging to the subject. Thus, Steiner’s “reflection” is not an abstract division, it is a unifying recognition. (Read the about page of this website regarding reflection here)

From Local to Global

Hand of God, by Auguste Rodin

Having established the necessity and validity of observing thinking from within, we can turn to what this observation reveals about the essential nature of thought itself. In the act of knowing, we don’t act as passive processors of information, we engage in a self-determined spiritual activity. When we observe thinking in action, we discover that it is identical with the very core of the “I”. The “I” is not the body, nor the sum of feelings, or even drives. The “I” is the active subject that thinks. In thinking, the subject and its activity coincide, and so the thinker is the thinking. This identity of the “I” with thinking is the birthplace of genuine self-awareness. Here the divide between knower and known is overcome actually, where we are the producer and the witness of the ideal content. We are united with what we know. Yet thinking, for all its self-sufficiency, is not complete in itself. It is one side of reality. Thinking is the active, formative, unifying side of reality. To become full knowledge of the world, it must seek out and unite with its counterpart. This other side is the given, perceptual content of experience, what previously was described as the precept. A precept without concept is completely unintelligible, and a concept without a precept is empty and does not manifest in the world. True knowledge arises only with the unity of the two. Thinking is what penetrates the percept, discovers the concept that belongs to it, and in doing so brings the hidden ideal nature of the thing into consciousness.

Thinking is a free act insofar as it is self-caused (both thought is free, and I am freely choosing to think), and it is my activity. It is necessary in that the connection is dictated by the content of the concepts themselves, and not on my subjective whim. There’s an important realization emerging. When I observe my own thinking, I see that the activity is mine. Meaning, in its self-production, it is local and individualized. Yet the content I am thinking, whether it’s the logical connection, or the mathematical truth, is not subjective of private. It carries a necessity and validity that is universal. As Steiner states: “The oneness of the concept ‘triangle’ does not become a plurality through the fact that it is thought by many. For the thinking of the many is itself a oneness” (p. 94). The content of my thinking is not my creation. I did not invent logic, or mathematical truth, I merely discover these things. For example, two plus two didn’t equal four once I’ve thought about it. How can it be that this non-personal content is the very substance of my personal act? My thinking is only “mine” insofar as it is of my agency, but in its content and form, it participates in a lawfulness that is above me.

“In thinking, we have given to us the element which fuses our particular individuality into one whole with the cosmos.”

—(GA 4, p. 94)

The subjective act of thought cannot be a closed loop in this case. It is a localized instance of a universal activity. One does not generate logical form ex nihilo; in a way I am tuning in to and executing an activity that is, in its essence, global. The local act is simply the individual performance. But the global act of thought is the very possibility of this performance. It is as if the local act is a performance of music, however the reality of the score is ideal. In the moment of thought — where I am fully active, yet wholly devoted to this ideality of thought — I experience that the activity powering my “I” and the activity constituting the ideal content are one and the same. Likewise, you do not think about a global thought (or, as Steiner calls it, a cosmic thought). You think it. Your local activity is the global, or cosmic, activity, becoming conscious at the point of thinking it. The global function of thought is in fact the inner nature of your own active being, arrived at by realizing that “my” thought is not merely “mine”.

“What is striven for in this book is to justify a knowledge of the spiritual realm before entry into spiritual experience… to show how an unbiased consideration… leads to the view that the human being lives in the midst of a true spiritual world.”

—(GA 4, p. 5)

The process by which the individual accesses this global, or cosmic, world of ideas is called intuitive thinking. Intuition, in Steiner’s sense, is the conscious experience, occurring within the purely spiritual, of a purely spiritual content. It is the act of inwardly generating or discovering a universal concept from within thinking’s own activity. Worth keeping in mind is that this process is not merely a passive reception of the ready-made Idea, it is an active engagement with the Idea of a thing, and with the world of ideality (also known as the spiritual world). When confronted with a percept, intuitive thinking sings and brings forth the specific concept that corresponds to it. In doing so, it individualizes the universal. This one idea is grasped by this consciousness, at this moment, in a form colored by the individual’s unique standpoint and experience. This individualized concept becomes a mental picture (Vorstellung), or in the moral realm, a moral intuition. Intuitive thinking is the mediating power that connects the local act to the global act. It allows the universal world of ideas to enter into the world, and enter into individual life. Through intuition, the thinker does not “apply” subjective thoughts to objects, he or she participates in the act of thinking by bringing the ideal content of an object into conscious relation with the given percept. The local act is therefore both mine and not-mine. It is mine in its performance and individualization, yet it is not-mine in its source and validity. Some may take issue with the term “intuition”, but it is completely justified. An etymological look will reveal it as literally meaning “in” (en) and “to look at” (tueri, as in tutor). What other name is appropriate for the activity of grasping the necessity of an object’s unity internally?

Spiritual Activity as Freedom

The task of intuition, or intuitive thinking, is to apply itself and become knowledge. When we seek to know something, whether it is a natural phenomenon, or a spiritual reality, or even a social situation, we are attempting to unite our thinking with the object’s thinking, or the objective idea which constitutes the object’s being. In other words, we seek to grasp the object’s generative thinking. In the act of knowing, we bring forth the concept that corresponds to percept. This process is a spiritual activity in its fullest sense. It requires the thinker to engage intuitively with the world of idea and to individualize the universal concept. The free human being is thus one who lives in such spiritual activity: thinking that is self-determined, moral action that springs from love for the ideal, and knowing that participates in the creative thought of the world. The ideal in question is not abstract and external, but a real possibility inherent in human nature. Ultimately, the man is not a product of nature or society, but has the capability to be, and rightfully should attain the status of, co-creator of reality. By developing the capacity for intuitive thinking, we become conscious agents of the spiritual world, realizing our individuality in harmony with the universal. This is the promise and the challenge of the current stage of consciousness. We must overcome alienation through self-knowledge, and recognize in ourselves the spiritual activity that is the source of both truth and freedom. Only when thought realizes itself to this degree, will we truly be free.

The significance of thought is revealed in its potential to bridge the chasm between ourselves and the world. In our current age, thinking has achieved great power in analysis, but this analysis is a loosening up of what was previously unified, by a new emergent capacity. The task is for this capacity to situate itself as constituting a whole once again; the imperative of the current age is to transform this analytic, observational capacity into intuitive thinking, thereby establishing it as a true faculty of spiritual activity. Thought must evolve from a logic which dissects, into a spiritual force which unites. It must undergo metamorphosis from a tool of the alienated “I” to the substance of a free spirit actively participating in the world’s becoming. In this metamorphosis lies a sincere responsibility and our highest destiny, for the next age will not be built by bureaucrats, or by capitalists, or by scientists, or by calculators. It will be built by thought which loves, intuits, and acts, by those who realize that true thinking is the first deed of freedom, and that through it, humanity ceases to be a passive spectator of cosmic processes, and wakes up to being in the world. Thinking for the next age will build ourselves from within, and impel ourselves to think from within the living ideas that brings forth the world.

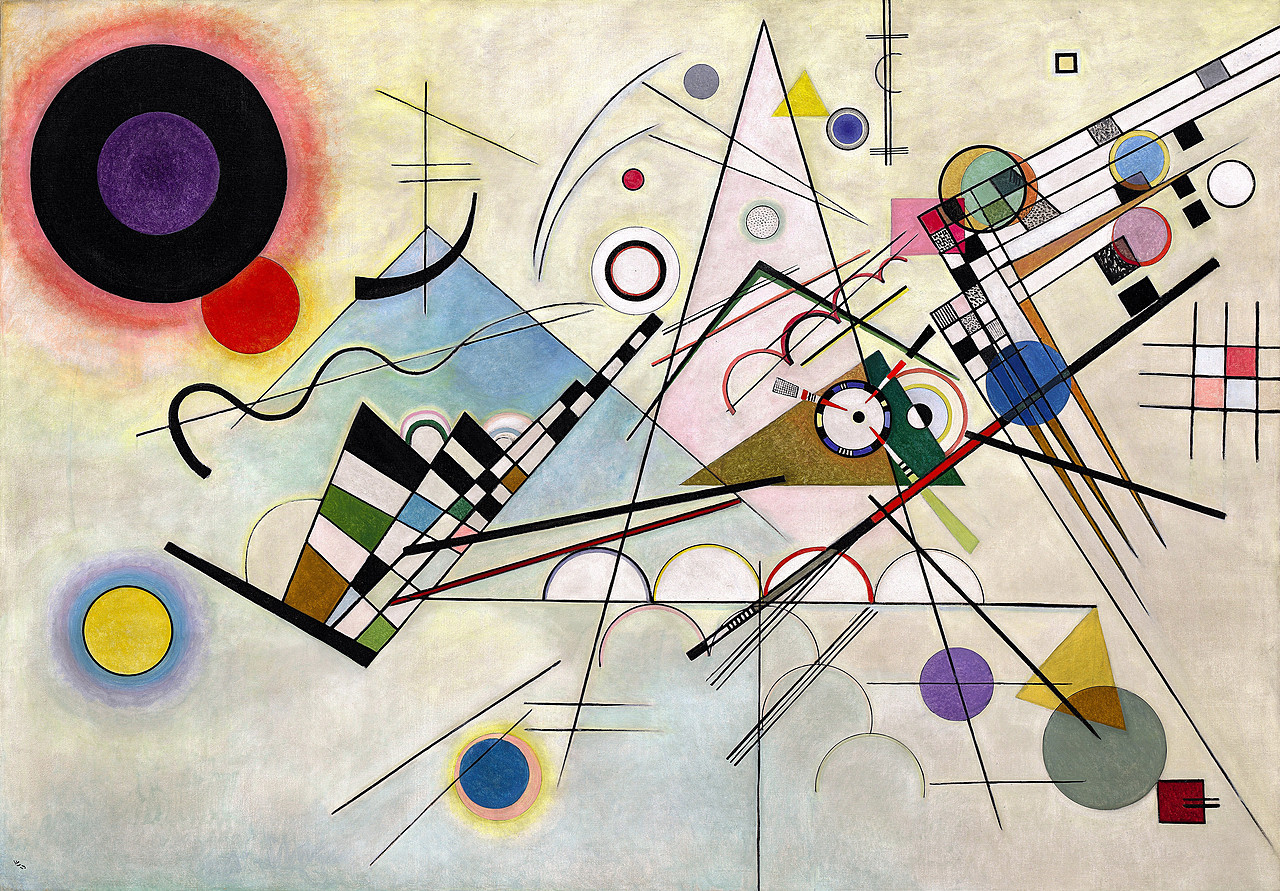

Composition 8, by Wassily Kandinsky