Introduction

Philosophy’s consideration is supposedly one which is both universally accessible, and universally accepting of contribution. There is an imperative for any valid domain that it be accessible to anyone regardless of background, and for this domain to relate back onto man, in such a way as to be receptive to the background of the contributing agent. As such, the question of how the domain of philosophy stands to exclude is not simply a sociological critique, but it itself a philosophical problem that strikes at its claim to truth, and it’s status as a valid domain. Nowhere is this problem more acute, or more personal for me as a thinker who happens to be African American, than in the tradition of German Idealism, and supposedly its indirect successor found in Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy. In the works of Kant and Hegel, and in the spiritual-scientific system of Steiner, we find some of the most powerful frameworks ever conceived for understanding freedom, humanity, consciousness, etc. Frameworks that explicitly aspire to universality and objectivity. Yet, embedded within these same works are characterizations of Africa and its people that range from apparent prejudiced ignorance to a placement “outside of History”. This creates quite a few seeming tensions, and conjured within me questions, which I have since reconciled, but wish for the reader to keep in mind in order to guide their own thinking and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions. Indeed, it only takes a few Google searches to come across the scathing words Kant and Hegel have had for an entire continent and groups of people. What differentiates them from their contemporaries, found in individuals like Linnaeus, if anything? How can such totalizing systems be so exclusionary? When we get to the more esoteric frameworks, such as with Anthroposophy, in what way are such thinkers (or in this case, “seers” perhaps) not essentializing the categories employed during their time and placing a kind of determinism upon individuals which are within categories? How are the individual and the particular group they belong to reconciled, what is that relationship? These questions go on and on, however the most important question guiding inquiry is this: how can one value the architecture of a system seemingly built, at least in part, with flawed and exclusionary materials? In other words, where do the descriptions of Africa, and this “race” of people (Africans), come from, and what does it stand to mean for the destiny of these people according to such philosophers and why?

The contemporary philosophical movement of Afro-pessimism offers a stark and logical response. “One cannot value such systems” is essentially the insight of thinkers like Frank B. Wilderson III. The standpoint of Afro-pessimism (hereby referred to as AP) is that this thing called blackness is not just excluded from, but is the constitutive outside against which Western concepts of “Humanity” and “Social Life” are defined. From this view, the problem of Africa in Kant, Hegel, and what appears to be Steiner is not an accidental flaw, but the revealing symptom of a structural antagonism. To seek inclusion or reclamation within their systems is, therefore, a kind of fundamental error. This article argues against that conclusion. What I propose is that the most rigorous response to this historical problem is not to discard these philosophical systems, but to engage in an immanent critique and subsequent reclamation, if appropriate. By carefully comprehending the claimed universal method of these thinkers and then appraising the claims they make, such as with Africa, one can correctly avoid “throwing out the baby with the bathwater”, as a matter of saying. If such contingent particularities of their historical consciousness exist and pervade their thought, we can successfully discover how, using their own logic, they themselves contain the resources for self-correction. Through an examination of Hegel’s claims, Steiner’s understanding of what “race” even is, and finally, the universal imperatives at the core of these projects, the solution does not lie in the aptly named pessimistic, self-destructive passivity of AP. If a solution exists, it exists within clarifying the universality these thinkers left behind as the inheritance of all mankind.

Universal Systems, Particular Blindness

Universal aspirations of European philosophy from the colonial period (let us say from the 1600s to the 1800s) did not emerge in a vacuum. They were conceived in a world being reshaped by colonial conquest, slavery, resource extraction, and so on and so forth. These are all second-order, or for the philosophically minded, conditional factors. I don’t mean to invoke “material conditions”, since this would be making a very huge blunder in grounding necessity. Rather, I would like to place the necessity within the mode of consciousness which came to dominate the West. Colonialism is not just the economic “machine”, it is also the expression of the intellectual current of the age, one which seeks to master the external world through abstraction, quantification, and mechanism, and to sever the human being from the living connection to its spiritual origins, and crystallize this spirit into a fixed logical system. This is the consciousness that built not only the steam engine and the stock market, but also the philosophical systems of Kant and Hegel. Kant’s critical philosophy, which aimed to find the universal laws of pure reason, and Hegel’s Absolute Idea, which comprehended reality as the logical system of Concept, are supreme intellectual achievements of this current. They represent the peak of mind’s capacity to create self-enclosed, rational universes. It’s therefore not a historical coincidence that this epoch of radical abstraction in thought coincided with the project of global abstraction in practice, otherwise known as colonialism. The same consciousness that reduced the world to categories and concept also reduced foreign lands to territories with qualities removed. Philosopher’s like John Locke, who theorized on property while helping draft the slave constitutions of Caroline, and John Stuart Mill, who defended liberty while administering the British Empire, were not hypocrites. They were thinkers whose insights into law, liberty, and individuality were shaped by, and in turn gave form to, this dominant, globalizing, and ultimately abstracting mode of consciousness. Their work reveals that the very concepts of modern Western freedom and universality were, from their inception, entangled with the logic of domination and exclusion required by the global system they helped to rationalize. This entanglement is evident not only in whom these philosophies excluded, but in the very conception of “individual” which was promoted. The subject afforded rights by Locke, or moral consideration by Kant (with a qualification we will get to) was a specific historical abstraction- this being the propertied, European male. This model of subjectivity was already a fiction, a selective elevation of one mode of being into a universal form. Yet, this fiction did not culminate in a true qualitative individuality universally. Nor would it be possible to rescue such a project, let alone aim to integrate into it. Instead, under the logic of the modern, abstracting consciousness they helped codify, the particular “Caucasian” subject has dissolved just as surely as the colonized “other”. What has emerged is not a universal qualitative individuality, but the quantified fungible unit. It is the interchangeable “man” of bureaucracy and markets, the “mass man” of José Ortega y Gasset, and the One-Dimensional Man of Herbert Marcuse. Fundamentally, it is the unfree individual. The philosophical projects of Locke and the like thus contain a tension. Their abstractions point toward a universal humanity, yet their historical instantiation served a particular, exclusionary order. At best, this means their philosophies are on some level incomplete as a result of a contingent birth untranscended. At worst, it suggests that the logic of abstraction, of the modernity which they contain, has in it from the very beginning a reduction of the human to a manageable quantity. This is the very possibility that enables both the rationalized “liberty” of the citizen and the rationalized exploitation of the colony.

Immanuel Kant’s work presents such a striking internal conflict between his groundbreaking universal ethics via the Categorical Imperative, and his own deeply held prejudices. In his writings Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, and Groundwork of Metaphysics of Morals, Kant writes, for instance, that the “Negroes of Africa” had received “by nature no feeling that rises above the trifling”. He goes so far as to tie moral character with biology, providing pseudo-scientific justifications for purported suitability for servitude. This was certainly not a marginal aside. It can be read rightly as a systematic attempt to ground human difference in natural law, directly contradicting the core principle he would later establish as the foundation of morality: that every rational being possesses an incalculable worth as an end in itself, as noumena.

Let it be known that this schema was not left unchallenged within Kant’s time. The philosopher was directly critiqued by a rigorous empiricist found within Johan Georg Forster. Forster, who had sailed with Captain James Cook on his famous voyage, wrote to Kant, correcting his blatantly wrong empirical commentary on non-European peoples. Forester’s first-hand observations from A Voyage Round the World presented a far more complex and human picture of Pacific and other indigenous societies, undermining the simplistic racial categories invoked by Kant. Within this encounter, one can observe a dynamic of the abstracting, classifying impulse of the foot soldier of modernity (in this case, Kant), being confronted by the concrete, experiential knowledge of the traveler-scientist (Forster). However, we too would be guilty of not affording another subjectivity, if we did not recognize Kant’s own evolution in thought. His later shift, particularly in The Metaphysics of Morals, surely can be described as a change of heart, but it is also Kant being compelled into self-correction by the logic of his own system. In this text, here, the philosopher who once catalogued racial destinies just 10 years earlier, comes around and condemns the institutions of non-European slavery, de-links moral character with biology, etc. He now constructs an edifice of right (Recht) that methodically excludes such empirical classifications, and condemns slavery as a fundamental violation of the Categorical Imperative. Slavery treats a person as a mere means rather than as an end (in this case, as a rational being), and so would make Kant the biggest hypocrite if allowing for such an acceptance. Moreover, it would mean he is failing by the very same standard that he set.

So what prompted this move? The move which severed moral worth from any biological contingency has established the universal “person”. Anyone who is subject to moral law is defined solely by the possession of practical reason, a faculty which, in Kant’s mature philosophy, admits no gradation by skin color. What prompted this move, is a demonstration of our initial claim of universality, if true, having the tools to rescue itself. The power of a truly universalizing philosophical system outgrows the flawed particular inputs of its author. Kant’s early racism was stupid, not just ethically, but philosophically, as a non-universalizable particular that could not withstand the formal test of his own categorical imperative. His later work shows the system expunging itself of this incoherence. The abstract drive for a perfectly rational system proved stronger than the empirical prejudices it initially absorbed. In Kant, we see the modern consciousness beginning to confront, and correct, its own exclusionary logic from within.

Hegel’s Africa

In terms of empirical contingency, Hegel’s system offers no such drawback. Within the majority of his work (barre what we will soon discuss), what you find is the lofty heights of abstract thought, the pure movement of the Concept. In other words, he arrives at his system deductively, unable to be tainted by empirical matters. This is precisely the appeal of his system, the fact that it demonstrates only what is necessary in logical form. His “racism”, so-called, is therefore a different order than Kant’s. It cannot be a biological prejudice smuggled into anthropology, because the very structure of his philosophy precludes biology, or nature, from determining or overdetermining Spirit (here to be read as the active principle of totality). Where Kant imports empirical racial hierarchies into his philosophy, Hegel’s Science of Logic (and Phenomenology of Spirit, although this does not offer any sort of key to understanding his thought and comes quite late in his system) develops a framework where Spirit is a universal potentiality. What this means is that there is no reality where biology, or any other contingency, effects the internality of a thing. Moral worth, in this context, can never be tied to biological characteristics. In a very rough manner, the opposite can be said, that the internality is what shapes the externality. However, this lends itself to needing qualifications and inviting misinterpretations, so it is better left unsaid. Regardless, what is to be emphasized is the universality of Spirit. This is why Hegel’s infamous placement of Africa “outside the compass of history” in the Lectures on the Philosophy of History must be read not as a racial slur, but as a specific claim within his system. For Hegel, “History” is a technical term denoting the process wherein Spirit achieves self-conscious freedom and externalizes that freedom in the rational, universal form of the State. His assessment of Africa is thus a philosophical judgment about the development of a specific form of political self-consciousness. What meets the standard of entering “History” for Hegel, is for a people to find a universality, and spread it. This universality is a self-conscious universality (meaning there is a mechanism of self-recognition) where freedom is law and vice versa, embodied in the rational state.

The very existence of concepts like Ubuntu, which articulates a conception of mutual recognition, demonstrates that many African civilizations already contain, at least implicitly, a seed of universality. African civilizations had, and have, a substance. All people do. What’s lacking is full actualization through the form of a rational state and codified law. Every man on earth is self-conscious and relates objectively to others within a group. But for a people to come together and form a state — one that recursively enforces and mediates universal principles of right — requires the collective recognition of freedom as law and law as freedom. In other words, African kingdoms had laws and governance surely, so ethical substance is not lacking. The objective institutions of a rational modern state were for Hegel. This state is defined by its capacity to recognize all subjects as abstract, right-bearing individuals before a universal law, rather than as members of a particular family, clan, or tribe. This is the transition from customary governance to constitutional right. Now that the standard is clarified for Hegel, this methodology explains his otherwise surprising engagement with the continent. Unlike the broad, derogatory brush of his peers, Hegel demonstrates a specific (if not flawed and limited) interest in African societies, referencing Ashanti and Dahomey. He is attempting to analyze them through his conceptual framework rather than dismiss them outright. His framework even possesses a logical aperture for recognizing Black political agency, most notably in his positive commentary on the Haitian Revolution, where he acknowledges enslaved Africans attaining a “concept of freedom” and forming a state. Such commentary shows, in principle, that his system could register and explain such an event as a moment of world historical significance, even if he did not place it central to his narrative.

As it relates to the claim that the African has not achieved the necessary “distinction between himself as an individual and the universality of his essential being”, Hegel is correct on this specific, developmental point. The sharp differentiation of the individual ego from the communal and natural whole represents an advancement of stage in the evolution of consciousness. This is the truth within his Eurocentrism. However, this should not be mistaken for a prescription of the future. It’s a description of a formal stage which aligns with the development of Concept, or in other words, vindicates the deductive result of Concept’s developmental path by finding it in the world. To observe that a particular form of consciousness has not yet emerged is not to predict it cannot or will not. Hegel’s own comments on Haiti (such as written on by Susan Buck-Morss’s Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History) should dispel the notion that “Africans” will never amount to anything, designated into an eternal state of nature. In fact, his own methodology teaches that every stage is necessarily overcome. It is a fact that every subsequent development of what Hegel calls “history” becomes the standard, lest it be destroyed by the truth of a further developed concept. What is claimed as the “standard” or the pinnacle of development must be, in some way or another, adopted by all states unless they face destruction. Consider this metaphor: when playing video games, META is defined as the most efficient tactic available. Such a tactic is a novelty of action, if only to be replaced by another META. In order to succeed at the “game”, you either have to adopt this “META” strategy, or come up with ways to confront it, lest you lose the game. This is essentially what has happened with the state form and consciousness found in Europe and the resulting reaction by the world that we call “modernity”. It follows, then, that a more “developed” logical structure does not equate to a higher human worth or a “better” humanity. It only describes a capacity for a certain kind of abstract reflection and institutional formation at the time of description.

Hegel is right, in concept, about these aspects of Africa. However, having established that the concept of state is a logical deduction, we must now confront the disquieting reality of his Philosophy of History lectures. Here, the unspoiled movements of the concept collides with the dirty, prejudiced empirical data of its time. In order to appraise world history, we need to use empirical data to trace the concept’s actualization in the world. We wouldn’t want it to remain an abstract schema floating in the sky, unable to enlighten us about what is. This integration with empirical data certainly doesn’t invalidate the deductive aspect of his system, but it does point to a failure in structural integrity, where philosophy is being supplied with biased missionary reports and colonial-era anthropology. You know, the kind of secondary literature available to a German professor in the 1820s, and so steeped in the racial ideologies of their time. As a result, when declaring “Africa” no historical part of the world, it is just as much validating a pre-existing colonial narrative with the authority of philosophy, as it is pronouncing a logical conclusion.

The lectures present a series of mistakes, each fueling the next. The first is Hegel’s description of the African interior as an “unknown Upland” with no internal movement, where the “Negroes have seldom made their way through”. Such a geographical error erases the millennia of complex history including Bantu migrations, the trans-Saharan trade networks which linked Timbuktu to the Mediterranean, the dynamic empires of Ghana, Mali, Songhai, etc. By rendering Africa geographically static, he manufactures the precondition for declaring it historically stagnant, missing the very same logical movements his own Science of Logic should have recognized as its own. The lectures traffic in sweeping, dehumanizing claims. Africa as a whole is painted as a place where cannibalism is customary, parents and children sell each other regularly, and there is “perfect contempt for humanity”, to quote Hegel. These tropes are drawn from the most sensationalistic and context-stripped missionary reports as the normative character of the race, when in reality, these were atrocities of war or famine. Philosophically, this serves the function of manufacturing an empirical proof that Africans exist in a state of mere sensuous volition, devoid of “universal spiritual laws” (like familial morality) that form the ethical substance from which the State immanently emerges. The brutalizing effects of the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade (which he notes) are then simplified as the essentiality of an entire continent.

The analysis of the “African religion” is just as much a failure. Most noteworthy is the fact that complex monotheistic and cosmological systems, such as Akan Nyame, existed. Cosmic systems are reduced into sorcery and fetishism, arguing that the African “commands the elements” and thus has no “consciousness of a Higher Power”. Additionally, he describes the ritual interaction with objects. In claiming, “if any mischance occurs… they bind and beat or destroy the Fetich”, what he effectively does is interpret a ritual interaction with a mediating vessel of spiritual force as literal transactional mastery over a powerless object. From the standpoint of abstract intellectualism, such an act indeed seems nonsensical. The burden of proof, however, still rests on Hegel to demonstrate that this interpretation is the correct one, that at once all people are “rational”, and that a whole category of people are acting in a way you deem irrational. The steel manned position is that they are functioning in a way which is intelligible, and that you have yet to figure it out. Verily, the case has not been made; the possibility remains that the ritual described is an engagement with the spiritual being within or behind the object, and so is an act of communication within an ensouled cosmos as opposed to crude domination. Furthermore, the “higher power” in such systems is often immanent in all things, a pervasive unity of being rather than a separate abstract deity. To accuse such a worldview of a lack of divinity or higher power is to miss a very foundational coherence. A coherence that, ironically, is very Hegelian.

While acknowledging intricate political rituals (for example, he mentions the sending of parrot’s eggs in Dahomey as a check on the king), he categorizes all African polities as despotic, held together by external force and the arbitrary will of a ruler. He fails to see the implicit constitutional principles within them. The Ashanti Empire, which he mentions, was a federation held together by a sophisticated constitution named The Great Oath, a representative council, and legal codes. Defining the State solely in its modern European, bureaucratic incarnation, Hegel in effect renders all preceding political formations, including those of Ancient Greece or feudal Europe, as preludes. However, he reserves for Africa alone the totalizing verdict of being on the threshold of World History, a present-tense exclusion. There is quite the inconsistency here with respect to Egypt, Chaldea, and India. For Hegel, these represent Spirit’s essential and revered childhood, but he frames their defects, such as the caste system, polytheism (which he accuses Africa of having), or theriomorphic gods, as necessary preludes toward the Greek and European realization of freedom. They are on the path, and produced monumental architecture, writing systems, philosophical thought, and so on that European scholarship could recognize as precursors to its own tradition, which it claims is universal. Africa is denied this dignified position as precursor. Its forms of consciousness are not seen as contributing to the dialectic, but as constituting a static ahistorical void beside it. The similarity in stages of consciousness are curious (from a purely structural perspective regarding the relationship between self and world, Africa and this or that cultural sphere might share similarities), alongside the valuation of a diametrically opposed kind. One is a noble beginning, the other is a nullity, a necessary “outside”. While one can argue the bankruptcy of a singular historical dialectic when confronted with the full breadth of human cultural forms, the correct line of argumentation, and what this ultimately proves, is that it is this particular narrative. It is not a neutral logical template finding its correlate in the world, but a specific substantive narrative of the ego’s journey to self-conscious freedom as it unfolds in a particular cultural stream. This narrative, which finds its zenith in the modern Germanic-Anglo world and its “consciousness soul”, has no internal place for Africa except as a constitutive outside, a spiritual “state of nature” against which historical consciousness defines itself.

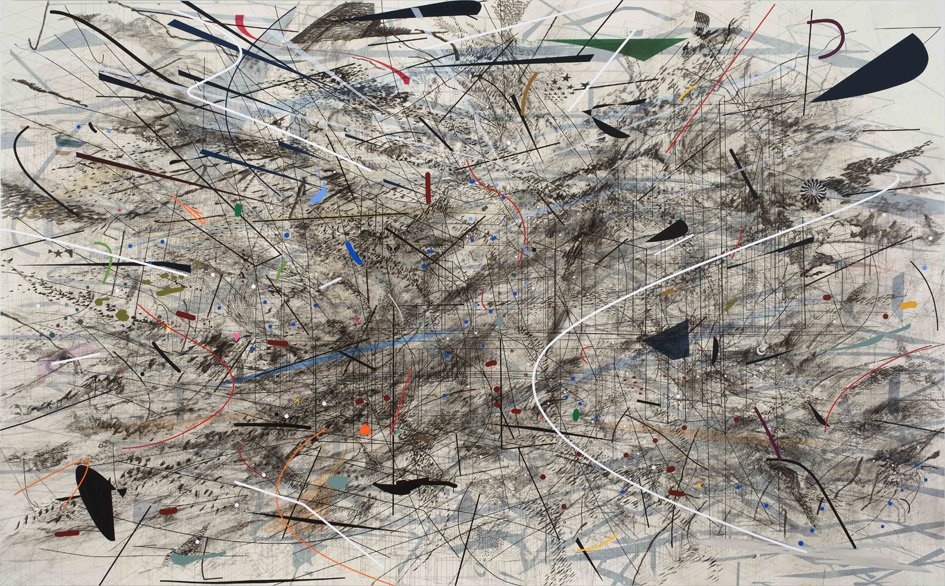

Black City, Julie Mehretu 2007

What one can thus accurately term Hegel’s philosophy is not racist in any biological-essentialist sense of a Locke or early Kant. Their racism is additive, being prejudices attached to philosophical systems primarily concerned with other questions (governance and morality, although questions which exclude certain subjects). Hegel’s failing is much wiser. It is “structurally” Eurocentric. His system does not include racist remarks on the basis of biological character, nor does it tie destiny to biology or other such contingencies. Its very architecture, including what results in the trajectory of World-Spirit, identifies the unfolding of self-conscious freedom exclusively with the Greco-Roman to Germanic-Anglo lineage. Structurally, there is a necessary “outside”, or a natural immediate backdrop against which History is defined. His system presents a specific substantive narrative which has no place for Africa, except as an immediacy and externality within the subjecthood of Spirit, resulting from its characteristic mode. Africa becomes this unhistorical ground because of its postulated placement outside state-formation. The Eurocentrism described here is not a moral failing or even a correctable oversight. It is the very expression of the consciousness identified earlier as the systematizing intellect, which seeks to master reality by subsuming it under a single, logical progression. In other words, Europe was the center of the world at the time, and in a sense Hegel is rightfully Eurocentric. His genius was in giving this consciousness the most perfect philosophical form, yet his system’s inability to integrate Africa, except as an excluded void, highlights a limitation. What it does, is describe what develops and that a thing developed along a certain historical path. But it cannot explain why this development manifested where and when it did, or how other cultural forms relate to it as anything other than precursors, negations, or points along its normative development.

Curious, even further, that modernity has “rescued” the status of Africa by claiming that we are all originators from this dark continent. Of course rescued, by providing leader assassinations, IMF and World Bank economic “adjustments”, and resource extraction. Contemporary thought, having internalized this Hegelian marginalization (insofar as Hegel is characteristic of the heights of this epoch’s attempt to make the world intelligible), now attempts a kind of rescue by claiming Africa as the biological cradle of mankind, placing it within “history” using the tools of empirical taxonomy and vague conceptions of society/organization. Yet this “rescue” often replicates the original abstraction: it venerates Africa as an origin point for the species, while continuing to deny the continent’s own historical subjectivity and political agency. Practices, such as the ones mentioned above, treat the continent as a non-sovereign contributor to the world, as a standing reserve of raw material and testing grounds of modernity’s tools of weaponry, propaganda, financial domination, and so on and so forth. The bankruptcy, is therefore not the single-line historical dialectic, but of the particular historical content that has been inscribed upon it. This story cannot account for Africa because it was conceived, from the outset, out of its absence. This itself has profound implications, which I will elaborate on in future articles. Ultimately, the ask is not to discard the idea of a spiritual-historical development of man, but to seek a more comprehensive framework, while keeping what works. One which can integrate the rigorous aspects of Hegel’s system, as well as the different, parallel, and specialized spiritual missions of humanity’s various cultural streams. This is the point at which the critique of Hegel necessitates a turn to Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy, which posits precisely such a differentiated cosmology of cultural souls and epochs. Steiner offers a model where Europe’s development is one specialized task among many, in a collective human journey, thereby creating a schema where Africa is no longer the constitutive outside, but a vital pole in a manifold spiritual ecology.

Anthroposophy

In order to approach Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, one must first distinguish it from the theosophical context from which it emerged. While sharing a lexicon (such as “root races, Lemuria [which, if you are familiar with the name, proves my point. It was a name picked up by theosophists, which is why Steiner used the name. It refers to the theory regarding the proposed continent of Lemurs, then was adopted by theosophists to identify the third root race, only to be picked up by Steiner to describe an epochal Earth condition. I personally think it should be called Thermia or Pyria], Atlantis”, etc.), Steiner’s project has differences, some drastic, some minor. Theosophy, as articulated by Blavatsky, often presented racial and cosmological history as a sequential hierarchy of collective spiritual evolution, acting as a map of humanity’s past and future. Steiner, though initially working with this context, broke off from theosophy and began his own movement. For him, these historical and racial differentiations were not ends in themselves, but pedagogical contexts within a larger project devoted to the development of individual spiritual freedom and cognition. In order to do this, he developed a kind of phenomenology of consciousness and freedom to outline a path for the individual “I” to achieve spiritual autonomy. One can read Anthroposophy as a post-Kantian, post-Hegelian endeavor. One which accepts the critique of naive metaphysics and the historical development of spirit, but insists that conscious, methodological inner experience can extend the boundaries of knowledge beyond Hegel’s “Absolute Knowing”, into an active participatory comprehension of the spiritual realities, or the ideal world. His system is less a doctrine, and more a methodological imperative for the evolution of human cognition.

Steiner’s most challenging, and most relevant, contribution is his model of human difference. To a philosophic audience, his statements on race can be reframed from what appears to be bizarre esotericism, into a historicization of the human form. His proposal is that what we observe empirically as racial differentiation is the surface effect of deeper, epochal shifts in the constitution of human consciousness and its relationship to the spiritual world. The main premise is that human consciousness and its embodied form are not static. They have evolved through distinct, qualitative stages. In earlier stages (which he terms Lemurian, Atlantean), human perception and self-awareness were configured differently. Overall it was, more immersed in spiritual and natural forces, and less individuated. The varying layered constitution of different groups crystallized around these different orientations to spirit and the world. Therefore, “race” is a phenomenon of spiritual history. It is a transient condition of the embodied soul, and a consequence of humanity’s collective spiritual past. This presents a few challenging questions in the face of the framework. For example, if one seeks to transcend race, how can they follow a model which provides such detailed, and often times hierarchical-sounding descriptions of racial characteristics? Doesn’t this simply create a spiritualized racial essentialism?

This is perhaps the most central and valid challenge. A common critique labels Anthroposophy as a form of “spiritualized racial essentialism”. However, the system’s own foundational texts define race in a way that actively dismantles this charge. Race is explicitly termed a transient historical remnant, or a ladder to be used, and then discarded. The core ethical command for the system is the soul’s emancipation from racial peculiarities. Importantly, it institutes an ontological split between the development of the immortal soul and the development of racial forms. To mistake Steiner’s description of these fading forms for a prescription of identity is a misguided reading of a system whose stated goal is to render the very concept of race “meaningless” and form communities based purely on Spirit. In fact, Steiner predicted (it’s not so much a prediction as you could tell this would happen) that the end of isolated tribal lineages and increased “blood mixing” would herald the close of an age where certain forms of instinctive knowledge were tied to “unmixed blood”. This is not only to invoke the kind of miscegenation which conjures to mind modern notions of race (White, Black, Asian), but also to include the kind which has tribes in regional proximity to each other mixing (whether by domination or trade, it does not matter). The loss of these capacities was not a degeneration, it is to be taken as the clearing for the dawn of the rational age. It enables the possibility of a higher, conscious clairvoyance. By nature, this conscious clairvoyance is a spiritual strength achieved based on the individual’s development of the “I”, thus shifting the locus of spiritual power from the physical body (and biological contingency) to the sovereign spirit.

In the initial encounter with Steiner’s framework, that is, after the euphoria of finding someone whose project I could get behind, I looked deeper into his comments on race. The fundamental question I wanted to answer, and the question which will also be of importance to differentiating us from previous attempts at “universality”, is how is this different from Hegel’s Eurocentrism? Steiner also uses terms like “immediacy”. Hegel places Africa outside history as a state of “immediacy”, yet I critique him, and so isn’t there an inconsistency? The answer I’ve arrived at is that the difference is structural and teleological. Hegel’s judgment is a philosophical verdict within a relatively closed historical dialectic. While he describes a stage, he offers no internal mechanism for Africa to enter History, except through the formative (and often times colonial) influence of Europe. Steiner is prospective and built on karmic/incarnational fluidity. The “immediacy” or particular spiritual configuration is a starting point for the soul’s journey, and not a final verdict. The individual “I” incarnates into a specific racial/folk context for specific learning, precisely to develop what is lacking. Furthermore, the entire framework is design for its own dissolution. Hegel’s Eurocentrism is a conclusion. Of course, a critical philosopher must acknowledge the performative contradiction at play. Using the charged language of race in the early 20th century, no matter the intended technical meaning, inevitably invites the opportunity for misinterpretation and misappropriation, no matter how much one clarifies (and Steiner did. Multiple times, he has said that the races he describes in his lectures are not commensurate with the races we find in the world today, and moreover, that we are all essentially the same. The coming of Christ put a formal end to the significance of blood and calls on us to go beyond this contingency). The system’s intent is anti-essentialist, but its historical entanglement with the language of racial science means its effect in the world has the opportunity to reinforce the very patterns it seeks to transcend. Rather than this acting as a refutation of the operative principles at play, it is more so a sober acknowledgement of the space between intent and reception. The goal of reclamation, described earlier, is one way to navigate this space. Surely it is the one which is employed in this article, and one I will continue to explore in future projects. Nevertheless, to fully engage with the critique and assess this space, we must examine Steiner’s specific characterizations of Africa and the functional role of folk souls within his cosmology. This will help us unveil the principles in his model.

When Steiner discusses what he terms the “African” soul-mood, or folk soul, his descriptions often center on a preserved relationship to spiritual immediacy and the natural world, words not too dissimilar to Hegel’s. He describes a consciousness less differentiated from the environment, more directly immersed in the rhythms of life and the force of the astral world. While the European “consciousness soul” spearheaded intellectual abstraction and ego-development (a process he described as both necessary and dangerous, I mean just look at the state of Europe and America today), the African cultural sphere retained a connection to a more unified, participatory consciousness. This preserved quality is not a relic in any pejorative sense, but a counter-balancing reservoir for humanity. Its mission is to sustain this connection, providing a spiritual counterweight to European intellectualism and holding a seed of perception that is key for man’s future post-intellectual evolution. This is the mechanism of the folk soul. In Steiner’s system, these are akin to cultural-spiritual ecosystems. Race provides a particular set of conditions, particular challenges, affinities, (a tendency toward intellectual analysis, rhythmic communal life, or maybe a nature-oriented perception). The incarnating individual “I” chooses, based on its karmic needs, to be born into a specific folk soul environment to work with those specific qualities. The folk soul is comparable to a curriculum, where the “I” is a student. The ultimate purpose of this curriculum is for the student to master, and then outgrow it. Therefore, to identify with the folk soul, or to love the transient qualities of one’s race, is to fail the assignment. Success is measured by the ability to lift oneself out of particularities, and integrate their lessons into a liberated individualized spirit.

It must be noted that the cultural epochs named by Steiner are not these rigid historical cages which preclude other cultures and nations from success. We can look to the example of China. Within the anthroposophical framework, China is not assigned a singular, dominant epoch ever. Yet China is not only a civilization of immense antiquity, and continuity, it is also a decisive global power, which is shaping the material and ideological bounds of this century. What this clarifies for us is that what seems anomalous to the model, does not act as a refutation. China’s trajectory demonstrates that the spiritual mission of a cultural sphere is to develop its own distinctive qualities, whether in statecraft or philosophy, across vast stretches of time. Its current rise highlights Steiner’s point, that epochs describe specialized developmental tasks and modes of consciousness. That an epoch is named for a culture only describes where this tendency most prominently emerges. Any idea which conceives of the cultural epochs as a “ruling of the world” is misguided, as is the conception of these cultural epochs as placing certain cultures and civilizations in the “dominator” role. History is, after all, a manifold of parallel and interacting spiritual phenomena, each with its own contribution to the whole.

The doctrines of reincarnation and karma are what change Steiner’s historic model into a pedagogy for the soul. Where Hegel’s totality unfolds through nations and states across world history, a part of Steiner’s totality, is the journey of the “I” across soul history through successive incarnations. Reincarnation ensures that the folk context one is born into is a “classroom” of sorts. A soul incarnates into a specific racial-folk environment (or classroom) by karmic necessity to balance experiences, or develop lacking faculties and the like. What this means is that the spiritual characteristics Steiner associates with a group are not essential traits binding its members, but are more comparable to a palette of potential lessons available to any soul that enters that environment for a time. What Hegel could only see as a fixed “stage” of World-Spirit becomes, in Steiner’s system, a recurrent experiential modality within the infinite curriculum of individual spiritual development.

Note: I am taking it as given the existence of reincarnation as a phenomenon, for the purposes of engaging with Steiner’s system. However, for those who remain unconvinced, it is worth nothing that this is not an arbitrary assertion. Serious empirical research into the phenomenon, most notably the decades of cross-cultural case studied compiled by psychiatrists like Ian Stevenson, or even the University of Virginia’s Division of Perceptual Studies, provides a body of anomalous data. This includes children with detailed, verifiable memories of previous lives, which challenges strict materialist/physicalist paradigms. This research does not “prove” Steiner’s cosmology, surely. After all, it could be the case that a subject is tapping into some collective bank of experiences and not in reality being that person, however, is this itself not a kind of reincarnation? What this literature certainly does establish is that the concept of reincarnation is not merely a poetic flourish. It is a genuine hypothesis with empirical backing. The framework of Anthroposophy offers one coherent way to make sense of such data.

There is a clear relationship between the “I” and the temporary racial condition. Race is ultimately instrumental and temporary, and the “I” uses the racial-folk context as a learning apparatus. Let us give a concrete example of this framework. The Black American struggle, culminating in movements led by figures like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., can be seen a collective enactment of this anthroposophical principle. Here was a people whose racial designation was used to construct a brutally limiting environment of subjugation and exclusion. Their spiritual and political achievement did not find them identifying with this imposed racial identity, opting instead to master its most painful lessons and then transcend it. By invoking the universal ideals of personhood, equality, and inalienable rights, which were principles embedded in the very constitutional fabric of the nation that excluded them, they did not end up becoming “white” or European. They instead compelled America to recognize a failed universality it had professed but failed to embody. The “hierarchy” of race was invalidated and thereby ushered in a more universal standard of citizenship for all, effectively lifting the whole society out of the particularities of race each person finds themselves in.

This leads to the clarification that within Steiner’s system, to be born into a racial or folk category predicts nothing essential about the individual’s spiritual constitution, capacity, or destiny. The individual ultimately has their own developmental agenda. One soul may incarnate into a specific racial context to develop patience through oppression. Another may incarnate there to develop the strength to lead a struggle for justice, and yet another may be there to cultivate artistic expression from within a particular rhythmic tradition (hence the common adage of white musicians being met with “he must have been black in a past life”). No racial category carries a deterministic spiritual signature for the individual, and more than that, there is no significant spiritual content within “race”. The characteristics Steiner describes are tendencies of the environment, which follows that the “African” soul-mood of immediacy or “European” drive for abstraction are spiritual climates. But within each climate exists every conceivable type of seeker, thinker, and pioneer. The ultimate freedom of the “I” is proven in its very capacity to manifest in ways that defy any and all collective typologies.

“In our age, primary attention should not be paid to racial descent but rather to the living impulse expressed in the words of St. Paul: Not I, but Christ in me.”

— Rudolf Steiner, 1911-03-07 GA124

Reclamation

The preceding analysis leaves us at an impasse. The tensions within German Idealism and Anthroposophy, having traced their grand, universalizing architectures, have been laid out and confronted. The Afro-Pessimist challenge in this context draws an illogical conclusion. Discard the tools, for they were forged for your exclusion. Yet the different, more demanding, path has presented itself. If the works of past contributors to human knowledge can be compared to ovals, and we seek the wheel, then the task is not to reject the oval and attempt to invent the wheel anew from scratch (ending in futility). No, it is to see the flattened sides of Eurocentrism and the non-uniformity of racial hierarchy as constituting our given material (holding onto the oval metaphor), and using the principles of geometric reasoning inherent to its creation, work it into a true circle. This is immanent critique, the application of a system’s own highest standards and rigor to correct its flaws, internal contradictions, and appraise the system as being worthy or not of reclamation. Hegel’s commentary on Africa (not touching on India, China, his thoughts on music, etc.) represents a kind of contingency which denies subjectivity and due process to Africa at worst, and completely mischaracterizes it at best. However, we’ve arrived at this conclusion using the standards present in his system itself and not via a moralizing critique or external standard, this being the demand for a concrete universality that can account for all of human being. The structure itself has an unrealized potentiality, demanding that its claims of universality be made genuinely universal. Steiner has informed us that there is an imperative in spiritual emancipation, such that it clarifies that racial descriptions must be read as fading diagnostics and not eternal truths, certainly not the kind which makes the individual unfree.

Such projects are often met with skepticism. Why labor within frameworks that are supposedly scarred by the pathologies of their age? The answer is quite simple. A truly innovative thought or creation, whether it be the Categorical Imperative, the Speculative Method, or the concept of Freedom, does not remain the property of its originator, nor was it ever “theirs” in the first place. If it is genuine, it becomes part of the commonwealth of human consciousness. And nor is the genesis solely in the individual. When one finds that they are inspired, they truly are in-spirited. They have an insight from another awaken and resonate within their own capacity for reason and spirit. In that very moment, the innovation ceases to be theirs and becomes a living tool for creation. Likewise, as a thinker shaped by the West and standing in critical relation to its failures, I do not engage as an outsider. I engage as a participant of its continuum, claiming the right to separate the method from the madness. Likewise, each new world historical “innovation” of a culture becomes the new standard of the world, and the world must adjust. Modernity, did not merely offer innovations, it established the new global standard by which all other societies would be compelled to measure and recognize themselves. The innovations it provides, such as the capitalist nation-state and the ideology of the sovereign individual, coalesced into a totalizing system. This system was then universalized by competitive necessity and of course colonial imposition. The world was re-made in modernity’s image, rendering all alternatives of being either assimilated, marginalized, or rendered historical. When a new world historical innovation appears on the stage, it will also alter the world, whether it be a change in consciousness, or a new technological paradigm (which will fundamentally alter our being such that it can be described as a change in consciousness. Take that how you will.).

The definitive proof that this reclamation is neither naive nor futile is in the history I’ve mentioned before: the Haitian revolution. The enslaved Africans of Saint-Domingue didn’t petition for entry into a French universalism that hypocritically excluded them. What they did was seize the universal principle of liberty itself, and through their struggle, compelled the world to witness its instantiation. Was this a “European” tool they used? Or was it an exposure of the European failure to grasp their own tools’ logic? Haiti demonstrated that the most potent critique of a flawed universal is in its very enactment. In the same spirit, the work of immanent critique today is to take the various “ovals” of philosophies and frameworks and, through the application of their own very standards, work them into the circles they should be, rather than re-inventing the wheel. In spite of this, an apparent final philosophical test is yet to be faced. It is in the face of the claims of Afro-Pessimism.

The “challenge” of Afro-pessimism

The Slave Ship, by J. M. W. Turner, 1840

The Afro-pessimist position, mentioned earlier as being articulated by Frank B. Wilderson III, stands as more than a critique of racism or exclusion. It is a political doctrine that states that Blackness is constituted as the logical negation upon which the very category of Human, and subsequently Social life, is built. Blackness is not an identity among others that has been excluded from a pre-existing humanity, but is rather the constitutive outside against which humanity defines itself. The slave represents the ontological anti-thesis to personhood insofar as, following along the logic of modernity, they are mere objects in a position of social death, as opposed to laborers. “Social death” here, implies a position of ontological exclusion from the bounds of personhood and relations that define social life. From this perspective, the “entanglements” traced in Kant, Hegel, and Locke are logical necessities of a world structured by this anti-Black antagonism. The universalism proposed by such thinkers are not unfinished, they are in actuality finished closed circuits from which their very coherence depends on the barring of Blackness. Immanent critique would be diagnosed as a category error, or mistake which has a logically impossible end. If the Afro-pessimist is correct, the not only is the endeavor of “not re-inventing the wheel” and reclamation difficult, it is futile.

To this challenge, one must begin with a concession. Afro-pessimism rightfully describes the historical record and the failed instantiations of these philosophies. It provides the most cogent explanation for why the Enlightenment’s “Rights of Man” could coexist with the Middle Passage, or why Hegel’s World-Spirit could consign Africa to an ahistorical void, and why any universalism birthed within the context of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (hereby referred to as TAST) carries the scent of death. Individuals such as Domenico Losurdo might have previously documented the savage dialectic of modernity, particularly of the Liberal paradigm and its grim underbelly. For example, it may seem paradoxical that alongside liberalism, you find the very illiberal policies of slavery, colonialism, genocide, racism, and so on and so forth. But AP takes this insight and recognizes it as an ontological principle at work. This principle is claimed to be that the concept of the modern human is born from the historical negation of the Black.

Additionally, the more perceptive among you might have noticed that I have avoided defining race in this article. This is another thing which Afro-pessimists are insightful on, the historical formation of the concept. The TAST was what created what we now understand as blackness, particularly as a category of what they claim is social death, as the foundational negativity of modern political ontology. The economic system of the modern age required a new pseudo-scientific (with the aims of justifying itself institutionally) taxonomy of human value. Thus, race becomes a category in the grand systematizing project of the Germanic-Anglo epoch, as an expression of its abstracting, quantifying consciousness. A brief genealogy of justification will show that the concept has always been philosophically unstable. Its justifications began with empirical taxonomy, retreating into metaphysical genetics (any grouping of what makes a race a race becomes “begging the question”), and now it has circled back to a crude, pre-critical apprehension in the form of “just look, people are different!”. From its inception, race has been a problem of category error, chasing a material basis that it can never truly find. In essence, race can be defined as a deliberate confusion of categories born from the TAST. This must be distinguished from ethnicity, which is a perennial human reality (although just as historically contingent. specific ethnicities have not always existed). Where ethnicity concerns lineage and culture, race is a modern sign that appeals primarily to the epidermal character of man within a socially determined reality. This distinction is important since it allows us to recognize the Black American ethnicity, which is a real historically forged cultural identity with its own traditions, struggles, and ethnogenesis, as a creation born from the imposed racial category of Black in America, without conflating the two.

The above are indispensable parts of AP’s claim. However, AP runs into a very big contradiction almost immediately. In its totalizing diagnostic rigor, it inadvertently replicates the very metaphysical closure it ascribes to modernity. It correctly identifies how modernity constructs the Human through the negation of the Black, defining blackness as a position of social death. But it performs a self-negation. It deprives the Black of historical subjectivity and potentiality. AP freezes the Black in the position of the object, the constituted outside, and in doing so, denying the very possibility of a conduct that is not always-already captured by the “grammar” of slavery. The very lack of a normative project is itself telling, insofar as for thinkers like Locke, their conclusion that blacks are inferior is a result of modernity. The very same can be said about AP as a modern verdict that mirrors the kind of closure it supposedly critiques. This“freezing” is especially evident in its engagement with Frantz Fanon. The notion of “ontological non-being” was extracted from Fanon’s work Black Skin, White Masks by AP. The “zone of non-being” mentioned in the text is a lived negation to be worked through, resulting in the creation of a new humanism. AP’s reading freezes this moment into a permanent condition, disabling the Black subject. Compare this to the figure of Malcolm X, who exposes this rejection. He began with the same negativity. With the erasure of the slave name and the replacement of it with “X”, marking a new, open subjectivity, he was under no pretenses that he was not constituted, in part, by a slave system. However, he used that negativity as the beginning of a new universality, moving from Black nationalism towards a broader human solidarity found in Islam. AP, in contrast, seems perpetually stuck at the moment of recognition, wallowing in this moment, seemingly inept.

While one may accuse me of ad hominem, the question raised by the life choices of theorists like Frank Wilderson points to a genuine tension in the unity of thought and being. If the anti-black world is truly total, and all cross-racial relations are corrupted by the grammar of slavery, what is the status of Wilderson’s own life and relationships? He is, after all, married to a white woman, and operates within the very “white” field of academia. In the end, AP’s greatest strength in its unflinching description of the anti-blackness found within modernity becomes its weakness. Elevating social death from a historical condition to an ontological fate builds a cage around the subject, denying them the tools of their own liberation, and in the end, in hopes of being a theory in the name of describing impossibility, ends up canonizing it.

Here, my critique echoes Jean Baudrillard’s diagnosis of the postmodern condition. He argues that the masses respond to the overproduction of social and political meaning with a silent majoritarian strategy of absorption and neutralization. A kind of passive resistance that implodes meaning. Similarly, one might argue that AP, in its totalizing negativity, performs a theoretical hyperreality. Mapping the grammar of slavery with such exhaustive precision, its profound description of social death becomes a simulation of that death, or in other words, a closed intellectual system where all potential resistance, or normativity, is pre-emptively nullified as either naive or complicit. Like Baudrillard’s silent majorities absorbing and deflecting all messages, the AP framework can absorb all historical instances of black agency such as Haiti, the Civil Rights Movement, and Malcolm X as mere epiphenomena within the unchanging structure, thereby neutralizing their significance. Put this way, AP does not merely describe a condition of impossibility, it performs a simulation of that impossibility, mirroring the very absorptive, negating logic of the modernity which it critiques. It’s a very poignant form of theoretical surrender. The depth of the analysis is mistaken for the finality of the verdict.

Conclusion

Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, Kehinde Wiley 2005

At this point, we should return to the initial question: how can we value philosophical systems built to be exclusionary? We have examined the architectures of Kant, Hegel, and Steiner in an effort to explore their claims and discover what is to be valued. The AP response is to declare these systems irredeemably corrupt, saying “we can’t value them”. Declaring the very tools of universal reason to be poisoned at the source by the ontological crime of the TAST, it renders reclamation of such projects worse than naive- it’s a psychological coping mechanism for those unable to face the void. I have argued that such a conclusion, for all its rhetorical force (perhaps forceful to a pessimist, maybe), is itself a profound error. It is a theoretical dead end that, in the name of critique, delivers an addictive reliance to the very totality it claims to describe. Against this closed circuit of impossibility, the open-ended work of immanent critique must be posed, finding its most far-reaching expression in the often-misunderstood system of Rudolf Steiner. While Kant and Hegel may provide initial frameworks, it is in Anthroposophy that we find a metaphysical architecture explicitly designed for the task of transcending contingencies. Anthroposophy does not shy away from the historical reality of “racial” differentiations, whether born from the TAST-era consciousness, or from before then. The ultimate goal is to dissolve transient qualities and create community based on individual spiritual maturity. This approach provides the tools to actively overcome essentialisms and exclusionary frameworks in the development of one’s own being. Therefore, the solution to the problem of exclusion is not to be found in AP’s passive cage. It is in the active, disciplined labor of working with what you have, in order to build what should be.