Searching but not seeing, we call it dim.

Listening but not hearing, we call it faint.

Groping but not touching, we call it subtle.

These three things can not be investigated any further–

Therefore they blend and become one.

This one thing:

Its highest point is not bright;

Its lowest point is not dark.

Continuous and unending!, it can not be named;

It returns to non-being.

It is called the form of that which is without-form;

The image of non-being.

It is called confusing and indistinct.

Meet it and you do not see its beginning;

Follow it and you do not see its end.

Hold fast to the Way of the ancients

In order to master the present moment.

The ability to know the ancient beginning–

This is called the main principle of the Way

—Dao De Ching1

Introduction

The monkey’s paw of narrative is often that, for as much one wants to convey a particular story, competing narratives tend to be just as true as the one emphasized. At first, this multiplicity seems fatalistic. In the face of manifold stories and frameworks, how can one be the authoritative report? Northrop Frye has brilliantly pointed out this fatalistic tendency in the domain of literary criticism in Anatomy of Criticism2. He accused criticism of having fragmented into a clash of determinism. Pre-made ideologies, such as Marxist, Freudian, Jungian, and Neo-classical having made their battlegrounds the home of criticism, the work of the critic turned into the work of projecting the allegiances of the critic onto the work itself, rather than for the purpose of comprehension. And truly, this retreat of objectivity into multiplicity, into the mere assertion that one among many frameworks is the real one, is fatalistic. As soon as the report of a work is finished, there is immediately a kind of lack constituted in the very conveyance of the report, a realization that the report is haunted by what it excludes. One that is, of course, supplemented by the inclusion of other reports, as a band-aid to the problem. The indifference found within the claim that this one framework, in contrast to these other many, is the one framework, is truly doomed to fatality. The reason being that it is an ignorance of the highest kind: a deliberate and premature foreclosure, one that is arrogant and not found within the essentiality of the work, or object. The adherent of a single framework must ignore not only the legitimate insights of rival frameworks, systems, and narratives but, more fundamentally, the necessity of those rivals. On the other hand, the assertion that all frameworks are correct is just as fatalistic, posing itself as a tolerant pluralism. To declare all perspectives equally valid is to neutralize all of them, reducing serious conflict to mere difference of opining. The frameworks are not just different, but they are different in unique kinds of ways. This blind universalism doesn’t acknowledge the reality that each framework is exclusively claiming the totality of the development of the work. And so this view commits a different kind of ignorance: it abandons the search for truth, or connection to the work/object altogether, settling for a passive cataloguing of differences. It sees the multiplicity but denies the struggle within it, the very struggle that signals something real is at stake. This is the fatalism of indifference, where the friction from differentiation is smothered into a formal collection. My very wording gives away the solution to this problem- differentiation of what? In the first place, the very fact of multiplicity is a good sign, since it is a clue that hints at some unitary genesis, some generative act which created this multiplicity in the first place. And likewise, Frye’s response was to invoke a new approach. Frye intended to approach literary criticism as a theory of literature derived from the total structure of literature itself. He attempted to step back from the battle of deterministic frameworks to uncover the generative principles that made literature possible in the first place. The many are not the source, they are the manifestation of a prior, unitary movement that has differentiated itself. The problem, then, is not how to choose between stories or critical schools, or frameworks, or lenses, but how to discover a generative principle from which the story, and the frameworks for judging the story, emanate, and stand with that which they gain meaning from. This is what I aim to. More precisely, the same approach Frye realized is the correct way forward, applied to my intellectual pursuit, is the perfect vehicle which conveys the narrative of my transition from Hegel to Steiner.

The story of this or that individual can, similarly to a narrative, be interpreted from different frameworks, with all perspectives holding the seed of truth of the life of that individual. At once, my life story is the story of a musician, the story of a scientist, or scientifically minded person, the story of an appreciator of the humanity, and the story of an unofficial comedian (which probably has to do more with being American than any individual attribution) to name a few. However, once the higher unity of these narratives and reports are grasped, this situation is not viewed as a monkey’s paw, but as the opportunity for revelation, a testament to something created. This became the central pursuit of my intellectual life: to move from observing the myriad frameworks (the very battle Frye catalogued) to seeking the single, dynamic ground that makes frameworks possible at all. Likewise, this ground, or process, in the world (read: uni-verse), is the same process which is reflected in me as an individual.

A brief stint of my teenage years was spent reading, watching, and trying to parse the meaning of everything I could get my hands on, no matter how foreign or crazy. I’m ready to declare this attitude the furnace powering my search, and the most important outlook any given individual can have in life. And so I was led, almost gravitically by principle, as rain drops towards earth, into the realm of philosophy. This thing called “philosophy” made promises to me about how to understand and comprehend the world. Implicitly, it made promises of teaching me that principle in the world that I was seeking. I jumped from phenomenology, to politics, to epistemology, and finally to Marx, propelled by a series of failed promises to teach me, which rather than left me in disappointment, only fueled the aforementioned furnace, so to say. In hindsight, I don’t regret any of this period. It’s for the very reason that I have experienced my particular past, that the seed of truth wrapped in each encounter developed not only my intellectual life, but the person I am as a whole, and the person I aspire to be. It was Marx, really, who was in a sense the one that baptized me. Baptized me to the corpus of the only individual who made the genesis and unity, described earlier, the sole subject of his work: G.W.F. Hegel. This, in addition to what I can only call a very emotional, religious moment many years ago, where I retroactively describe it as actually feeling and grasping the unity of being, to the point where it brought me to tears, (which is another story for another time), prepared me to read the works of Hegel.

The Peaks and Valleys of German Idealism

Gustave Courbet, The Stone Breakers (1849)

The Stone Breakers is here to represent the spiritual moment in physicality (depicting labor here, but not exclusive to it) before entering a philosophic system.

Hegel’s project did not arise out of the ether, he was responding to something very important during his time. The response was to the fundamental crisis in post-Kantian philosophy: the separation between thinking and being, or between subject and object. This philosophical trend of Kant’s is known as subjective idealism, and the critical-philosophy.

Firstly, a brief overview of ideality, and what idealism is, is necessary. I can forgive myself for the brief overview of these monumental thinkers, but what I can’t forgive is overlooking key details in an overview of this brevity. The reason a working comprehension of ideality is necessary, is because the trends characterized by idealism circumvent many of the more basic positions in philosophy, positions which are not covered in this article. When one says the “Idea” of this or that thing, a subjective idealism, or an objective idealism, an understanding needs to be conveyed as to what kind of standpoint this “Idea” is. Idealism, contrary to the notion that it denies the physical world, is the philosophical position that the formative whole is prior, ontologically, to it’s constituted parts. It asserts that the organizing principle or totality (if all is truly unified, the organizing principle and the totality share a very intimate relationship), is more real, or on a higher level or priority than those aggregate elements. For example, a family isn’t merely a random female, a male, and a child. Those parts arranged by the ideal, or concept of “family” as a functional unity that determines their form and connection, a principle of kinship, shared life, and mutual responsibility to the whole, which shapes the roles, bonds, and identities of its members. That’s what a family is; the individuals become mother, father, child, or sibling not through biology alone (although it is through “biology”, or the external world/nature that this happens), but by participating in this living, purposeful whole that gives their relations and meaning. The individuals find their specific roles and relational significance only within this prior, unifying idea. Ideality is the active structuring force of reality itself, from Kant’s subjective categories to absolute Spirit unfolding in the world. Any true philosophy has this moment of ideality, as Hegel says below: (And this is a bit premature, but I can’t help myself, Steiner radicalizes this further: the Idea is not logic, but a living spiritual activity whose true knowledge necessitates the movement from “thought”, as unified with abstract thinking and generative process, to perceiving its being, or creative act, directly. This fulfills Idealism’s promise by moving from philosophy to spiritual science).

But the truth of the finite is rather its ideality. Similarly, the infinite of understanding, which is coordinated with the finite, is itself only one of two finites, no whole truth, but a non-substantial element. This ideality of the finite is the chief maxim of philosophy; and for that reason every genuine philosophy is idealism. But everything depends upon not taking for the infinite what, in the very terms of its characterisation, is at the same time made a particular and finite. For this, reason we have bestowed a greater amount of attention on this. distinction. The fundamental notion of philosophy, the genuine infinite, depends upon it. The distinction is cleared up by the simple, and for that reason seemingly insignificant, but incontrovertible reflections contained in the first paragraph of this section.

—G. W. F. Hegel, Encyclopedia Logic3

And so we find ourselves with Kant. His philosophy emerged from a crisis of certainty. Earlier in the timeline of man, it was believed that man experienced thought and perception as unified with the world’s essence/noumena/being (all three are terms hold essentially the same functional role here). But by Kant’s time, consciousness had become more self-enclosed, the I experienced itself as alienated from the external, objective world. And so, with rigorous honesty, he analyzed this condition and concluded that what we can know are phenomena, which are the appearances structured by our own innate cognitive categories (you might know them as the forms of intuition: space, and time, and causality). The reason this is termed the “critical philosophy” is because it did not seek to build a positive system about reality, instead, it undertook the critique of pure reason. It was an investigation into the boundaries and valid domains of human knowledge. The task of this critique was to judge what reason can and cannot legitimately claim to know. Kant’s project withdrew from the attempt to know ideality, or spirit, and the supersensible, declaring it off limits to theoretical reason. In the sense that it is limitative and self-examining, it is establishing a critique, or trial, for reason, that forbids it from entering into transcendent speculation. I was informed by my friend Warq that a comical result of this is that in Dreams of a Spirit-Seer, Kant is very indecisive on Swedenborg (a mystic who could perceive ideality, or spiritual realities), jumping from “this is bullshit” to “ok maybe this could be real”.

This “thing-in-itself” (Ding-an-sich), or the external world, remains outside our grasp because we cannot get outside our own subjective apparatus to know reality directly, according to Kant. You might recognize this perspective as the essential expression of everyday modern consciousness today. It’s quite shameful that in terms of intellect, the prevailing orthodoxy of our time has yet to seriously contended with Kant. Instead, it urges a weaker claim: that because our perceptions are mediated not even by the categories of understanding, but merely by fallible sense organs, we can never truly know reality. We have managed to inherit Kant’s conclusions, the unknowability of the thing-in-itself, while abandoning the rigorous critique that led him there. And so Kant had established that cognition is limited to phenomena. The thing-in-itself, or noumena, is declared unknowable. This created a dualism where thought was confined to the categories of the subject, and that properties are sourced from the I, the subject, onto the object. To put it another way, Kant recognized that reason seeks an ultimate ground, or unconditioned cause, something free from both the chain of causality, and the chain of conditions (such as the vetting process of the categories and forms of intuition) which is bound with the subject in the knowledge-process. He sought what governed the phenomenal world. And so this “unconditioned unconditioned” is the absolute, self-sufficient being that would complete the edifice of knowledge. God, the totality of noumena, freedom, reason, the soul are all contenders for this unconditioned. However, Kant made this formulation a regulative ideal, a necessary goal that guides and structures our inquiry but can never become a constitutive object of knowledge. To claim knowledge of the unconditioned world would be to transcend the very conditions of possible experience, which is impossible for Kant. The search is both innate and futile within his framework. It is dead on arrival.

Although these are harsh words to formerly name this trend, it is properly known as subjective idealism. All knowledge is contingent on the forms and categories of the subject. The properties we attribute to the world like causality, aren’t discovered in the object, but are contributed by the I. There is a split between the subject, which is thinking (engaging in generative activity), and on the other hand an unknowable reality. Kant correctly described the thinking subject’s feeling of separation from the world, but mistook this historically conditioned state as an absolute epistemological (what we can know) limit. The critical philosophy creates a yearning for the unconditioned, that immediately declares itself hopeless in achieving, and so the Spirit of the Kantian is one of dialectic, of restless contradiction. Subsequent thinkers struggled with this divide. Philosophy was trapped in what Steiner would call, a “mere thought-system about the world” unable to claim it was knowing reality itself. Thinking was seen as a subjective activity, the activity of the ego, not connected to the world’s objective essence, or noumenal reality. Because of this, there was a deep implicit striving in philosophy to reunite with the spiritual wellspring of existence, of being, to overcome the feeling that the human spirit confronts a foreign external world. Hegel ultimately sought to heal this rupture, and would go on to reveal that the true character of the unconditioned unconditioned, the principle in, of, and out of this world, is reason.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), known as the “last great system builder”, was a German philosopher whose systematic work represents the pinnacle of German Idealism, and the pinnacle of philosophy. After studying theology at Tübingen, he worked as a tutor and university lecturer in Jena, Heidelberg, and finally Berlin, where he served as professor of philosophy until his death. His major works: The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), The Science of Logic (1812-16), and the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1817), were published relatively late in his life and career. Hegel’s dense, demanding system aimed to explain the possibility of knowledge, and unify all domains of knowledge including but not limited to logic, nature, history, art, religion, and philosophy, within the self-unfolding of this thing called “Absolute Spirit”. Hegel saw the restlessness inherent in Kant’s system and aimed to resolve it by reconceiving the unconditioned. For Hegel, the unconditioned is not a remote “thing‑in‑itself,” but the very process of mediation itself. It is Reason in it’s self-active unfolding. This Reason is not a subjective faculty of the individual thinker, but the active, creative force of the world. Hegel hoped to demonstrate that when we think, we are not merely manipulating private ideas, but participating in the same logical activity that generates and structures all of reality. Thus, when the philosopher arrives methodologically at a concept such as quantity, it is not a category imposed by the subject upon an alien world. Rather, it is the same quantity that objectively structures a chair, for example, out in the world. The chair possesses quantity as an attribute contained within its own being; the principle of the object is not sourced from the subject but discovered in the object. Therefore, philosophical thought isn’t confronting a foreign world, or totality, it traces the totality’s own self-unfolding, including the object as it is separate from us, and the subject as it is us. Hegel names the result of what thought, as generative process, has produced, the Idea (Idee). It is important to realize that the proof that this process of thought is not just in your head, is in the pudding of Hegel’s work, but also in the fact that Hegel’s project can be explained as exploring what Steiner calls a “cosmic thought”. The contrast to the in-your-head thought has led me to describe it this way: there is a “local” function of thought, and a “global” function of thought. They are one and the same for Hegel (with the clarification that this unity only occurs once one comprehends logical thought, and also a point which will be contested, at the begrudging moan of my Hegelian friends by the end of this post). The endpoint of the process is the Absolute Idea: the moment when Spirit achieves complete self‑consummation in and through human consciousness. In terms of the system, the object, or the world, is not alien, but the Idea in its otherness. Correspondingly, the subject is not confined to the finite I, it is also present within the object, since both are ultimately unified in an absolute subject-object identity.

Brief note on recursivity: any true system of totality has a moment or recursion. I wish not to exhaust the topic here, because I am saving it for my “systematizing Steiner” project. The reason Spirit must find itself is, because in a system of totality, in a system that describes everything, the end must return to the beginning enriched by the entire journey. The recursive aspect is not a logical flaw, but the mark of something living. The circle is called “virtuously” circular because it is self-grounding, mediates immediacy, and embodies freedom (self-determination). The circle is the logical form of this- Spirit determines itself by returning to itself out of its own otherness (however, the philosopher does not understand that this circle is only the very shape of self-conscious freedom). Since this totality’s (Spirit) knowledge is essentially self-knowledge, it becomes actual only by realizing itself in and through its other. Spirit, to be actual, must go out of itself, give itself form in an other (nature, history, institutions), and then recognize itself in that other. If this remained purely implicit, it would be the worst form of empty abstraction. Hegel’s system shows Spirit giving birth to the Concept, which creates the objective world, supposedly, only to then recognize the world as its own expression. This journey from self-externality to self-recognition is the process of Spirit becoming real to itself. What does it say that this Absolute, God, is capable of creating beings which recognize the Absolute, such that this Absolute is itself constitutive of them? We will leave that for another day. For the biblically minded, the ask of recursion in philosophy, is similar to the ask of Christ in Matthew 18:3:

And said, Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven4.

Christ is not saying to stay statically in an impressionable, child-like state. It is a call for a transformation of self-mediation from the mediation and lukewarm being of adulthood. For if it was truly a call to the former, the moment man becomes child, and child becomes man, the fall of man commences eternally. Not very optimistic.

Hegel’s method beings his exploration of philosophy in what is dubbed “presuppositionlessness”. Rather than, at this point, enjoying the pitfalls of other sciences, which take as given their object, one needs to keep in mind that the object of reason is itself. Since reason is turned in on itself, reason becomes both the instrument and the object of investigation. We can take this in comparison to Kant, who in his critical philosophy, needs a given, a presupposition, in order to critique in the first place. To think without presupposition is to allow thought, or reason, to generate and examine its own foundations. Reason is being used to discover reason. This “self-reflexive” starting point unveils what Hegel identifies as the three moments inherent in an all genuine speculation (note: speculation here is meant in the sense of “sight”, as in spectacle, seeing as reason does, not speculation as in arbitrary conjecture): Understanding, Dialectical Reason, and Speculative Reason.

Note: the number 3 is important here, for the reason that it is the number of recursion, talked about briefly above. The significance lies in its role as the minimal structure for a self-mediating return. [(1)Understanding- (2)Dialectical Reason]- (3)Speculative Reason. This third moment is where the circle closes: the outcome reflects on the beginning, showing that the initial immediacy was always already mediated. The process is recursive because the end reconstitutes the beginning, as justified and comprehended. The reason it is not one (which I hesitate to term “monad” for the confusion it may cause) is because a single term would be static, it would be unable to account for itself, it’s genesis, or it’s truth/ideality. It would also lack an inferiority and self relation, and therefore lack freedom and life. The dyad (from affirmation to negation, let’s say) would end in cancellation, or an endless oscillation like skepticism. It lacks the moment of upheaval, the moment whereby contradiction is resolved into a higher unity that preserves difference within itself. In Hegel’s system, the triadic rhythm is the logical form of self-consciousness and self-grounding. Spirit begins in immediacy, loses itself in otherness, and returns to itself as mediated unity. The recursive circle, where the end is the beginning made explicit, is what makes the system self-justifying and total. It doesn’t rely on external foundation, the legitimacy lies in itself. Thus, 3 is the number of recursion because it is the minimal structure for a movement that goes out from itself and returns to itself, having incorporated its own negation. It is the shape of a circle that is not empty repetition, but a spiral of development!

Understanding (Verstand) is thought in its fixing, isolating mode. It establishes clear, stable definitions and distinctions, treating each concept as independent and self-sufficient. The core operation of the Understanding is to assert that A = A and A != B. Things are defined by what they are not, universal concepts are produced by extracting a single property or set of properties from a concrete whole to create a universal, and it organizes the world into genera, species, types, laws, taxonomies, and plants. Bcause of this, the Understanding is indispensable for precision in science, law, character, and art, providing the fixity in the world. It is akin to the goodness of God, in creating determinate enduring things. However, what it does is treating these stabilized “concepts” as ultimate and self-sufficient realities, forgetting that they are abstract in the lowest sense of the word. Yet, if left alone, it renders reality static and dead.

Dialectic Reason (negative Reason) is the self-negating movement inherent in those fixed determinations. Every finite concept, when thought through (or procedurally generated enough), reveals its own limit and internal contradiction, thereby passing over into it’s opposite. This is not an externally sourced critique, just an emphasis on the indwelling tendency of all things finite. The law that life contains the germ of death, that pride precedes a fall, the dynamic force of the object (nature, history, thought). When isolated, this moment becomes an endless oscillation, skepticism, which sees only negation, but in truth, this moment of negation is entirely necessary for progression. In this stage, the maxim of Spinoza: omnis determinatio est negatio (every determination is negation) becomes explicit. Each fixed determination, when thought through, reveals that it’s very identity depends on excluding it’s other, and that this exclusion negates its claim to be self-sufficient. The finite shows itself to be finite only through its limitation, which is its negation. In the previous stage, this maxim was implicit and latent. Determinations operate in the Understanding as if they were purely affirmative, isolating each category and holding it static. Negation is an external limit (this is not that), and not yet grasped as internal to the concept itself. The Understanding implicitly relies on negation to define its boundaries, but does not think negation is essential to the thing’s own being. It can be said that meaning itself is negation, for what does it mean to mean, what does it mean to exist, than to stand out from the whole? In order to be something, it needs to stand in distinction to unity, otherwise it would not be intelligible in the first place.

Speculative Reason (positive Reason) is the unifying comprehension that follows negation. Or, if you want more Hegelian words; the site where both “sides” expel their negative coalesce and settle into a ground. The speculative moment is the moment whereby a concept (subject) and its opposite are seen as necessary moments within some higher concrete ideality, or truth. This result is positive because it contains and preserves what was negated. Spinoza’s maxim finds its final moment as it realizes that negation is also constitutive. Negation, which seemed to dissolve determination, is now seen as the very means by which Concept (subject) mediates itself with itself. Determination is negation, but negation is equally position. The concrete unity (speculative unity) emerges by virtue of the negation of negation. What is truly determinate is not a static point, but a self‑determining whole that contains its own negation as a moment within itself. Thus, “all determination is negation” becomes “all negation is (self‑)determination”. Accordingly, Hegel’s method is not a tool applied to reality from outside; it is the form of reality’s own self-thinking. Beginning “presuppositionlessly” means allowing reason to generate and overcome its own determinations, or in other words, to trace, without external imposition, the Absolute’s unfolding from abstract immediacy to concrete self-knowledge. It is the logical embodiment of Spirit’s journey. The immanent genesis of the totality begins not with empirical facts or dogmatic axioms, but with the most minimal, self-evident thought one can think, or rather can’t think: pure indeterminate Being. This empty starting point is the Idea in it’s abstract immediacy. From this, the speculative method, the engine of the Concept, is set to begin.

And so it does, until we arrive at the Concept. I will not rob you of the joy of struggling with Hegel until you “get it”, and chances are if you are reading this, you probably already do (either struggle, or get it, or have struggled to get it). What I mean to convey is that the development… develops, until we arrive at Concept. The concept is the active principle of self-determination through self-differentiation. Being the third section of the Science of Logic (the beginning of his system and exploration), the Concept naturally occupies the recursive position of self-mediation, mirroring the triadic rhythm present at every scale: immediacy, mediation, and self-mediation. It’s borderline enlightening when one grasps the echoes of reality with itself. The triad of the Logic (Being, Essence, Concept) resonates with the triad of the entire system (Logic, Nature, Spirit), and both, in turn, rhyme with the three moments of the speculative method (Understanding, Dialectical Reason, Speculative Reason). This is not mere repetition but a “recursive elaboration”, where each subsequent triad re-enacts the previous at a higher level of concreteness. For example, the nature of immediacy itself transforms as one advances. The immediacy with which the Logic begins in the Doctrine of Being, that pure, abstract presence, is fundamentally different from the immediacy encountered in the Doctrine of Essence. This is already a mediated immediacy, an appearance that presupposes an internal ground or reflection. This transformation demonstrates that immediacy, or being, is not a static starting point, but a living moment that is continuously reconstituted and enriched.

The telos of this process is the Absolute Idea. This is the point where Concept has fully externalized itself (as Nature), and returned to itself (as Spirit), now possessing self-knowledge. Spirit recognizes the entire odyssey, from Being to the complexity of civilization and its fruits, as its own activity. For Hegel, this realization is absolute freedom. Freedom isn’t an arbitrary choice one makes, it is self-determination in accordance with rational necessity. When the philosopher grasps the system, their thinking ceases to be a subjective reflection on the world, and becomes the very activity of Spirit thinking itself. This is the culmination, where the thinking subject and the object thought (generative process) are to be understood as one and the same. The Absolute Idea is this self-consummation of the system. It is the beginning, which is the abstract Idea, or Logic as Idea as Subject, gone through mediation where Nature is the Idea as Object, and finally returns to itself through Nature, through the world and externality, recognizing the object as its own activity, and returns in the form of Spirit, or the Idea as Subject-Object. The concretely self-comprehending Idea having mediated itself through all of reality, forms a virtuous circle where the origin is justified by result, and the result is fully explicated by origin.

The moment I comprehended a fragment of this, it felt as if a long chapter of my life had finally concluded. Not to mention the point where my good friend Antonio Wolf5 walked me through the Science of Logic late at night, up until the point of Infinity, or the time I cried while reading the Lesser Logic due to the grandeur of existence, or the time I almost fell down the steps after being enchanted by Hegel’s writings on gravity in the Philosophy of Nature. The comprehension of the system heralded for his time a completion and the closure of the circle of Philosophy. Hegel brought the old form of philosophy, which wanted to comprehend the world through intellectual concepts alone, to its final unsurpassable conclusion. As we return to the initial topic of frameworks, genesis, and ideality, Hegel’s system can be said to be the framework of frameworks. It does not propose a partial perspective, but rather it proposes the self-comprehending totality that derives every possible category of though and form of reality, from a single self moving principle. Logically, it incorporates and situates every other finite standpoint before and after it in philosophy, as necessary, but subordinate moments within its own development. The closure it achieves by circling back by its own beginning demonstrates that its starting point was already the endpoint in implicit form, thus becoming the self-grounding system that accounts for the very real possibility of systematic knowledge itself. It is a framework, the framework, that explains why there are frameworks, the narrative about why there are narratives, and the circle that knows itself as circle, to name a few examples.

It’s a strange thing that Hegel’s teachings aren’t exactly new. His core thought, that the physical world, or object, is the externalization of what Steiner calls cosmic thought (thought in it’s global function, as generative process), as the solution to the chasm of subject and object left by Kant, is in essence, identical to the foundational doctrine of Western esotericism and occult secret societies. The world is created and sustained by thought- divine ideas, archetypes, spiritual beings. Hegel didn’t arrive at this through occult initiation, but through rigorous philosophical reasoning. It did not matter, for example, that his roommate Fichte was a Freemason, or other figures in his proximity such as Reinhold were the same. Through naively observing this truth in the structure of reality itself, and systematizing it in his logic, he grasped this doctrine. The content of his philosophy is esoteric wisdom, but his method was public, rational philosophy. Hegel himself comments on the esoteric/exoteric distinction in the Lectures on the History of Philosophy, stating that such a distinction does not exist in philosophy, since the only necessary thing is the necessity of the ideas. One cannot hold onto an entire idea as they do a physical item. Perhaps this is why there is a tragic poetic irony, or correlation, in both the fact that Hegel’s own works were published fairly late in his life, and the grand system contain in his works were destined to be understood only long after his time. This is not in accident of history, but a necessary consequence of the gap between Hegel’s conceptual world, and the ordinary consciousness of his time. Hegel’s philosophy demands a thinking that has developed to its highest power, a thinking that can live within the self movement of itself. Yet, most people, even to this day, remain within a simpler, more sensory-bound form of consciousness. Thus, the delay in comprehension isn’t to be explained as a scholarly lag. It’s testament to the spiritual/intellectual development required to meet Hegel’s thought. His system appeared as a shadowy image of spiritual reality, cast ahead of it’s time. Its late reception reflects the slow collective awakening of human thinking to the level where Concept can be recognized not as abstraction, but as living spirit. In this sense, the tragedy is also a promise. What arrives too early for its contemporaries, becomes the foundational challenge for the future. Just as Alfred North Whitehead claimed that all of philosophy is a footnote to Plato, all of modernity is a footnote to Hegel. Every subsequent thinker has to contend with what he has put forward.

The Character of Hegel’s Project

The benefits of reading and understanding Hegel are numerous. Firstly, Hegel’s philosophy is the ultimate training room for thinking itself. Since the requirement is for a mind to move beyond the reliance of sense-perception, and to operate with absolute logical rigor and consistency within the realm of Idea, this strengthens one’s ability to think abstractly, independently, and, at times, creatively. Secondly, Hegel provides the most complete structure of reality and details how reality’s unfolding is possible in the first place. For example, understanding the relationship between the one and the many, the finite and the infinite, cause and effect. Familiarization with these categories goes hand in hand with the next point: to reach the peak (and limit) of philosophical thought. Hegel represents the path that the history of philosophy, and big questions in philosophy, have taken. Experiencing firsthand the culmination of this path is truly a transformative event. In learning how to think properly (such that it is one with the object, thought), your own thinking becomes transformed. You start to think speculatively. The final reason I will state, although not exhaustive, is that there is a liberation of Concept from being a dead abstraction. Hegel reveals Concept as living and moving. The empiricist, physicalist, or materialist views are undermined, and the mind is prepared to see thinking itself as a spiritual activity.

Given this, it is with immense respect that one approaches the greatest thinker of the 19th century, regardless of intention. However, there is an interesting phenomenon where the awe Hegel’s system inspires itself becomes a kind of piety, where the admission of its greatness is mistaken for a demand for uncritical reverence. As Steiner observed, “some people can’t imagine that when something in contrast to them is great, humour can also be retained about it, because people imagine one must unconditionally show a long face when one confesses to experiencing something great in a well‑known person”. This dignity often shields Hegel from the very kind of immanent critique his own method requires. This being a critique that does not diminish his achievement, but takes it seriously enough to discover where the system, in its perfection, points beyond itself. For Steiner, that “beyond” isn’t, nor can it be, a negation of Hegel, but the transition from the abstract, logical Spirit (calm down Hegelians, let me make the argument first!), to the living active poietic reality we inhabit. The rigor provided by Hegel contributed to the hesitancy by which I confronted aspects of his system I felt were unconvincing. Aspects which gnawed on my subconscious until I could firstly, finally articulate what I did not agree with, and secondly, until I found an alternative in Steiner.

The seed we begin with should be stated bluntly: Hegel’s cosmology was simply not convincing to me. The irony of this reason being unconvincing to the reader is not lost on me. However, it’s the truth! The more I mastered Hegel’s system, the more I gained an almost visceral dissatisfaction. Spirit for Hegel is abstractly lord. Meaning, there is a non-contestable power to its claim, but unless once submerges themselves in philosophy, this itself is not convincing in Spirit. Additionally, you are free to align with God, with Spirit, and in fact are built in a way such that being and goodness align, and certainly, it is good to align yourself correctly. But where is the elaboration on the work of Spirit beyond individual humans and sociocultural formations? This absence is because such a description lies beyond what Hegel aims to do, and what he can justify. His concern is the logical movement of Spirit toward self-conscious freedom, not the descriptive hierarchy of spiritual beings. And as a result, the cosmology is left feeling very flat. Because Hegel’s methodology has no place in the dialectic for the concrete life of higher and lower spirits, no place for beings who cultivate themselves and sacrifice their substance out of love to create the world. Such a living cosmology cannot be deduced from Concept alone; it requires a methodology of direct spiritual perception, the very approach Rudolf Steiner develops. Only this allows for a freedom more concrete than Hegel’s logical self-return. A freedom that participates in the creative sacrifice of spiritual beings. Who among us, after all, has a reverence for the lower orders of form, of the stones, plants, and animals, because we recognize they are the borrowed vessels through which higher spirits fashion bodies? Hegel surely doesn’t, stating that nothing in Nature is as worthy of veneration as human art. The person who has this reverence can truly be called a teacher, one we can all learn from. Hegel’s Spirit unfolds conceptually; Steiner’s Spirit lives, loves, and creates (resisting the urge to say life, laugh, love, especially in the context of all the white American suburban women who have found themselves drawn to the works of Steiner, of which Steiner himself predicted, funny enough). This difference is not one of degree, but one of kind. No, that it was not convincing to me is not convincing to you, but it did lead me to precisely outline and submerge myself in Hegel, in order to find out why he was unconvincing.

Hegel’s project seeks to be immanently generative, deriving all reality, from the self-movement of thought. Because its generativity is purely logical, it unfolds only what is already implicit in the starting point, and as such it is the logical explication of a closed system, not an open, creative act that produces genuine novelty. The outcome of this logical generativity is a supremely coherent, self-enclosed map of spiritual reality. Further, the very perfection of the map, Hegel’s system, its seamless logical closure, is precisely what reveals it as a map, and not territory. A living territory would possess an inherent openness, a receptivity to the novel and genuinely new. The Hegelian will object here and say that the system’s ceaseless self-negation is its openness. However, this movement is internal to the circuit of thought itself; it is the recursive unfolding of what was already logically enfolded in the starting principle. This “openness” is the motion of a closed circle, it is the closed circuit of thought’s own generation. A magnificent, self-generating logical process, for sure, but one that cannot receive anything from outside its own generative rules. This is not an argument against circularity or recursion as such, as I previously emphasized the need for such a thing, it is an argument about the kind of circle. Hegel’s is a circle of thought, thinking itself. Contrast this with the method of a Goethe, whose thinking enters into a receptive dialogical relationship with the phenomenon, allowing the thing itself to reveal its law and spiritual, or ideal, being on its own terms and not on the terms of Concept. What you find is that the former is a closed circuit of deduction, and the latter is an open engagement with being. Hegel’s perfection is that of the completed blueprint, not the perfection of the living world. The system is the shadowy image, as Steiner says, or the logical blueprint of the world’s becoming.

To understand the exact nature of Hegel’s system further, we can employ a metaphor Steiner offers: the relation of a shadow to the hand that casts it. Hegel’s philosophy is like a perfect, logical shadow. It’s coherent, definitely, but it is a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional living thing (this thing being Spirit). The living reality, which is Spirit, creative activity, is the hand. Hegel’s genius lies in deducing its every necessary shape, and connection. The foundational error made here is mistaking the shadow for substance. He devoted himself to the silhouette, believing it to be the source, rather than recognizing it as a derivative image of a prior living form. The philosopher then really works in a magical circle, drawn by this play of shadows, unable to turn and perceive the hand whose movement casts it. This metaphor clarifies the model Steiner suggests. The network of concepts forms a kind of boundary (he uses the word tablet) between sensible perception and the higher supersensible reality, placing Concept, or philosophy, as a kind of mediating term between sensible reality and the supersensible (through higher faculties). And so Hegel’s Concept and Idea aren’t descriptions of totality, they are mediating interfaces of it. In fact, this is the reason purely mental constructs like geometric circles, or algebraic equations, describe the physical world with an almost frightening precision (to the extent that the less enlightened among us say that the language of the universe is numbers). The correspondence itself is proof that the conceptual network constitutes the structural interface (tablet, aka Concept/Idea) between Spirit and Nature, or between the Idea as Other, and the Idea as finally returned. We don’t derive the concept of a circle from sensory experience, like observing a horizon. We generate it inwardly, and then a profound moment occurs where we discover that this inwardly generated form governs external reality. This shows the conceptual order isn’t abstracted from sensation, but is the formal boundary condition that makes coherent sensation possible in the first place. Hegel’s system is an exhaustive logical exposition of this interface. The power comes from describing the structural rules of the mediating boundary itself, the logic of the “tablet” (this is Concept). And so this is also why it can seem to explain everything! It’s articulating the rules of the game board. The effectiveness of its deductions mirrors the effectiveness of mathematics. There is a reflection of the formal ordering principles at work in manifestation, but here is a very important point: this never reaches the source of the game, to the players, or to the act of playing. Math can describe an orbit, but it can never tell you why a planet exists, why it moves, and so on and so forth. Likewise, Hegel’s logic can deduce the necessary relations of thought, but it cannot generate the qualitative fact of a planet’s existence/being, or the living impulse behind its motion. The map is flawless precisely because it abstracts from the living territory to its formal relation. Thus, what Steiner calls the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics” (and by extension, Hegel’s logic) doesn’t prove that reality’s highest point is the Hegelian Idea. It proves that Concept is the necessary lens through which a created, intelligible world becomes comprehensible to the mind and thought. Hegel described the lens with unparalleled rigor, then concluded the lens was the eye, the light, and the visible world all at once. This is partly why Hegel’s Spirit feels abstract and flat to me. When one studies only the shadow which is created by the hand, one misses the warmth, pulse, and purposeful movement, or telos, of the hand. Correspondingly, Hegel’s Spirit is Spirit as logical function, or completed syllogism, not itself the living community of creative, loving beings (not just humans), who actively cultivate and sacrifice.

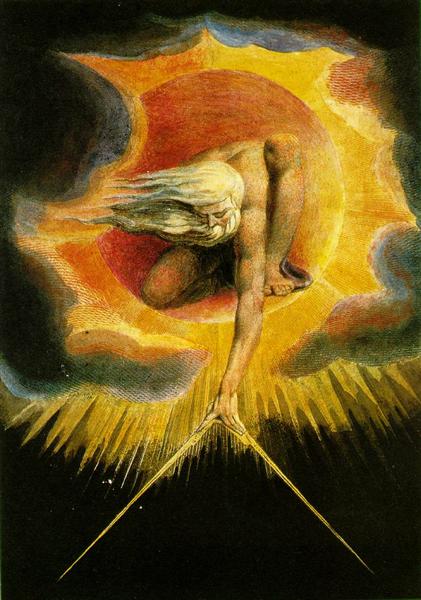

Newton, William Blake, 1795-c.1805

Blake’s Newton addresses a thinker so fixated on measuring reality’s blueprint, that he misses it’s living source and subsequently, the truth of reality itself.

Let us address the accusation of abstract, because it is meant in two senses. The first sense is the previously mentioned logicism, which will be elaborated on later. The second sense is in the fact that Spirit, for Hegel, remains in potentia until it is concretized by man, as opposed to Steiner where Spirit is very concrete as the hierarchies of spiritual beings. Here you see the seeds of the Promethean humanism that would be developed by Marx: the elevation of human consciousness to the role of necessary “actualizer” of the Absolute, implicitly via labor. In other words, the system is not a map, it is a map which reproduces its own methodological bias in every result. Having begun with logic, it can only ever find logic; having excluded any receptive relation to a reality beyond thought, it can only ever return to itself. What presents itself as reality’s self-unveiling is unveiled to be the self-unveiling of Hegel’s logical apparatus. For now, it may be helpful to imagine the distinction between Hegel, and what a post-Hegelian system needs to accomplish, as the difference between the map and the territory. While Hegel is detailing a perfect map, it is not the same as being in the territory.

“In that Empire, the craft of Cartography attained such Perfection that the Map of a Single province covered the space of an entire City, and the Map of the Empire itself an entire Province. In the course of Time, these Extensive Maps were found somehow wanting, and so the College of Cartographers evolved a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point. Less attentive to the Study of Cartography, Succeeding Generations came to judge a map of such Magnitude cumbersome, and, not without Irreverence, they abandoned it to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography."

—Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science” (1946)

The Problem of Contingency

The map’s perfection reveals its categorical limitations when held against the territory, or living reality. The first, and most telling, limitation is what I call the “Problem of Contingency”. Hegel’s system positions itself as the necessary capstone of philosophy’s history, yet it cannot explain why this necessary truth manifested in the early 19th century. It itself is a product of a spiritual and historical development that it did not, and logically can’t, immanently generate, only retrospectively justify. The system describes necessity, but its own existence is a contingent fact that escapes the method. Likewise, the Hegelian response is to exclaim that the contingent is necessary in actuality, that the historical appearance is some or other necessary actualization of Spirit at a specific stage. Philosophy is its own time apprehended in thoughts, according to Hegel, and so the system is not a timeless truth descending from nowhere, but the conceptual articulation of the historical substance of its era. The “why now” is answered by the Encyclopedic system, such that the publication of Hegel’s system is not a contingent event on the timeline of spirit, but itself the timeline of Spirit achieving self-recognition. Ultimately, this is a confusion of explanation with after-the-fact justification. The Hegelian response provides a brilliant retrospective rationalization but not a generative explanation. It can assign the event a necessary place in the logical narrative after the fact, but cannot derive the unique qualitative reality of 1817 Berlin from being. This is, in effect, a performative contradiction: the system, in explaining everything, cannot account for its own existence as a lived creative act. It can only incorporate it as a logical moment, stripping it of its vital truth. In addition to this, Hegel’s history of philosophy portrays itself as a vicious hermeneutic circle, stating that “the system appeared when it did because history had reached the stage the system describes”. This functions as an immunity against the genuine question of its own historical genesis.

A concrete example of this problem was brought to my attention, firstly by me. I was struggling with another problem I dubbed, the “Socrates and Buddha” problem, wherein I was trying to reconcile something in Hegel but found the solution in Steiner. What I was trying to understand was why specific individuals become world-historical vessels. For example, why Socrates, and why Buddha? On one level, their historical emergence seems almost contingent, depending on fragile transmissions from particular disciples. Yet their archetypal roles are necessary: Socrates embodies rational self-examination, looking outward, and Buddha, universal compassion and inner liberation. Inner and outer. The Hegelian answer is once again to say that the necessity works through contingency. Abstractly, and logically, this is the case. The essential truth of their teachings prevails despite historical accidents. But this remains a logical abstraction, a retrospective justification, not an explanation. Hegel’s grand “cunning of reason” is essentially a logical placeholder. Found within Steiner is an elaboration of the how turning into the metaphysics of Spirit’s agency. What Hegel calls World-Spirit, Steiner describes as spiritual hierarchies working through karmic agreements, and pre-earthly soul choices. The individual, in this case Socrates, Buddha, or a disciple, is not a passive node but a free collaborator. The soul chooses its path and conditions before incarnation; with inspiration requiring a receptive human vessel. Even the possessing of Spirit by man demands the individual’s consent. Steiner preserves Hegel’s insight, that necessity works through contingency, while grounding it in concrete processes and freedom. Suffering is not flattened into a logical node. The world we live in hears cries of anguish to God, the heavens, or anyone listening and receives this suffering as a substantive event, not as a mere contingency. Pain, pleasure, love, regret, insight, “eureka” moments, and more, are all felt by the whole. By subordinating all contingency into logical necessity, the Hegelian response collapses the living process of spiritual creation into a pre-determined script. In Steiner’s terms, it replaces the creative, sometimes improvisational, work of spiritual beings (the hierarchies) with an impersonal, logical automation. The “why” of Socrates or Hegel is reduced to a nodal point in a syllogism, not understood as the result of concrete spiritual guidance, karmic trajectories, and free spiritual agency working through historical contingencies. The Hegelian response thus embodies the very “flatness” of Spirit my initial intuition-turned-critique identifies.

The second time this was brought to my intention was when a friend introduced an alternative viewpoint: what if the History of Philosophy is actually the capstone of Hegel’s project? In hearing his explanation, it made sense, and I quickly and intuitively responded with the fact that this sounds like something Steiner’s project hopes to aim. After a day of thinking and talking about it, I agreed with him. He proposed that the History of Philosophy is the true capstone of the system, not just in subject, but in its reality since it “describes and enacts”. History, in this view, is the singular “description-enaction” where thought, and it’s object become one. Initially, this struck me as profound, and akin to what Steiner’s spiritual science aims at. This being a living unity of knowledge and reality. After a day, I disagreed once more, recognizing a subtle but decisive limitation. Even in this reading, the practical summons that emerges from Hegel’s history (the call to enact freedom consciously) remains a logical consequence of achieved Absolute Knowledge. It’s still, ultimately, a movement within philosophical comprehension. Thus, while the system can culminate in a transformative insight that bridges theory and practice, this transition itself is still comprehended and derived from the standpoint of completed philosophy. The “capstone” is therefore not an open, creative entry into history, but the final consummate description that logically necessitates a new form of practice. This is what preserves Hegel’s circle; that the end of theoretical history yields a practical imperative, yet both remain moments within the self-enclosed speculation of the Idea. The problem of contingency remains, although it might be a bit misinformed to call it a problem, since it’s more the lack of something the system can provide. And to fair, Hegel’s project is expressly aimed in solving philosophy, nothing more. The naming of it as a problem is moreso a politic move in order to urge Hegelians to see beyond, within the narrative of my own journey. Besides, even if the problem of contingency were resolved, a more fundamental limitation remains.

The Problem of Qualitative Immediacy

If Hegel’s system stumbles on historical contingency, then it faces a bigger problem when confronted with the raw being of the world, and the unmediated quality of living perception, which is something the logic cannot produce or capture. I will say it again: the logical method CANNOT generate or account for the qualitative immediacy, the raw, sensuous, being, of living experience. The system must treat the shock of color, the pang of grief, or the awe before a work like Moby-Dick, as mere logical predicates, moments in the self-determination of the Concept. Yet this formalism reaches its crisis not with sense-perception at the “bottom”, but with the very peak of spiritual concreteness: the encounter with a person. For Hegel, all individuality is conceptually mediated. A person is an individuality in principle. The system provides room for Christ as the necessary conceptual principle of God-man unity, as well as the Individual Individuality found within the structure of Universal, Particular, and Individual. Unfortunately, this Christ-principle is not the sensuous living person encountered in prayer or revelation. The immediacy of a who is always already reduced to a logically mediated what. The system may be able to generate the Idea of Christ, but it cannot host the encounter. Thus, in its treatment of its own most supremely concrete individual, the system points implicitly to a domain beyond its formal grasp: the domain of non-Conceptually mediated personal being. This is not a failure of Hegel’s Christianity as much as it is a necessary result of the formalism of the Concept. If logic can’t hold the living Christ, what is it to hold? Only his shadow. The formalism described here in full clarity is that since all objects are apprehended in and through their logical relation as necessary, universal, and mediated by Concept, Concept’s organization and giving intelligibility to content (hence shaping the object) is a formalism. Concept only encounters objects as structured and generated by itself. This is what we might call the formalism of the Concept. Everything must be translated into the currency of logical relations. As a result, the system is structurally blind to the very datum of consciousness, which is the very real, almost startling, given presence of sensation and feeling. This is a point-blank categorical exclusion demanded by Hegel’s sovereign, generative thinking. The map is drawn entirely in the ink of mediation; it has no symbols for the immediate, being of reality. Therefore, it can describe the logical necessity of sense-certainty as a failed form of consciousness, but it can’t originate the sensation itself. This explanatory deficit reveals that thinking’s sovereignty is bought at the price of excluding the most intimate layer of being. The problems of contingency and quality converge to reveal the final lack: life.

Note: The sophisticated Hegelian here might offer a rebuttal, “Life isn’t missing from the system! It appears explicitly in the Science of Logic as a deduced category of the Idea, the moment where the Concept begins to grasp itself as a self-organizing totality”. For Hegel, this logical category is the truth and essence of life. However, this very defense proves the critique. Hegel provides the concept of life, its logical schema, but not the living reality itself. This is the ultimate expression of the map-territory divide.

The Convergent Failure of Both Problems

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him.

Let us re-establish what Hegel’s project is, in light of this. It is the exposition of the Word, that flawless logical blueprint, the Logos as the complete ratio and relational grammar of the universe. After all, the entire Science of Logic can be read as an onto-logical proof of God. This is the God before creation. Hegel’s system is this divine logic, self-contained, and self-justifying in all its grandeur. Given this, Goethe’s final lines in Faust Part II, Chorus Mysticus6, points to what the logical Word cannot accomplish on its own:

All that is transient

Is but a parable;

What is inadequate,

Here becomes an event;

The indescribable

Here is accomplished;

The eternal feminine

Pulls us upwards

—Goethe, “Chorus Mysticus”, Faust Part 2.

These lines conclude the entire Faust drama, spoken by a mystical chorus. Hegel, the philosopher, sees the world of becoming. He sees birth, growth, decay, death, and he correctly interprets it. He sees that these fleeting moments that are coming to be and ceasing to be are not the ultimate reality, they point to a higher ideality. All that is transient, is but a parable indeed, one that Hegel has deciphered, showing how every finite thing is a moment in the self-unfolding of the infinite Idea. In this, Goethe and Hegel are indeed fellow travelers. However, the inadequate becoming an event is a stage which philosophical logic cannot achieve. It is the moment of realization and incarnation, where Hegel by his own standard, or method, must cease. Because he must cease here, the “event to be done” is Spirit’s historical unfolding, grasped retrospectively by philosophy. Above all, as the famous saying goes, the owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk. For Goethe, the conceptual blueprint, no matter how magnificent, is inadequate. It lacks the power to become an “event to be done”. Hegel’s system is not wrong about life per se, it simply offers life as a specter. It is a chronicle of past reconciliations written in the dried out ink of logic, as opposed to an encounter with the present, living creative act. Its very completeness is its sterility, and what results in what we identify as the fetishism at the heart of the system. Hegel sought Spirit in thought and found it there. His intention was quite noble and very profound. The intention was to transcend the human subject in thought and align its consciousness with the objective, creative World-Spirit. Yet, in an ironic reversal, he did not use logic as a medium to connect with living Spirit, instead he surrendered himself to the logical Idea, making the completed system (Absolute Idea) the ultimate object of his devotion. As Steiner argues, he committed a “fetishism of logic”. He correctly discovered Spirit within human thinking, but then made the categorical error of believing “that this spirit of human thinking, when developed to its highest power, is the World-Spirit” (GA 108)7. Thus, he surrendered to the pinnacle of ideation, not to the ideal creative source that produces the very capacity for ideation. The living generative reality of Spirit was replaced in his system by the worship of its own flawless shadow. The tool is the idol. Hence, the system becomes a monument to its own methodological triumph, a self-enclosed sanctuary where Logic is the supreme activity of God. That living, suffering, sacrificing, creative reality of Spirit, the very same Spirit Hegel claimed to unveil, retreats into the inaccessible beyond, visible only as a silhouette cast upon walls. The philosopher, being left in a temple of sublime shadows, mistakes the play of forms for the presence of divinity. Hegel’s philosophy articulates the perfect, living plan of the world, but it still remains a plan. It is the Word that has not yet spoken itself into flesh, the ratio that has not yet suffered the risk of incarnation. This ultimately is the chasm between the map and the territory. Hegel gives us Logos in logical purity.

The Ambassadors (1533), Hans Holbein the Younger

Holbein’s The Ambassadors represents a world of perfectly mastered symbols (notice the tools of measurement). Yet at its feet lies a distorted skull, or the undenaible reality of death: an unassimilable contigency, and the immediacy of memento mori. Death may be the most intense, and of course most easily accessible, non-negotiable instance of qualitative immediacy. Every person needs to contend with their own mortality. Even so, it can only be seen truly by shifting one’s perspective away from the brilliant surface of the map. So too must we view Hegel’s logical construction to grasp the living Spirit it occludes. Hegel famously critiqued the phrase “Spirit is a bone” in the Phenomenology of Spirit as the error of misplaced concreteness, the dead end of finding Spirit in the world. Ironically, he did not escape crafting it’s logical twin: “Idea [here meant as generated reality] is a syllogism". It’s a great irony that this skull represents that very same critique as self-applied.

The consequence is a constitutive, ethical-aesthetic blindness. Because the system cannot host a genuine encounter, it fails before the very realities it seeks to spiritualize. It can rationally reconstruct Melville’s posthumous recognition, but it cannot feel the weight of his obscurity or recognize the divine inspiration (and trust me, Moby Dick was divinely inspired) as a living current. The tragic particularity of suffering and the surplus of meaning in genius become logical nodes in a syllogism, never events to be lived. I think it is fair to call this a limitation, at this point. The limitation reveals its own imperative. If the perfect blueprint feels lifeless, and if the flawless logic cannot account for its own genesis in history, or its failure before a crying heart, then the task isn’t to refine the blueprint. It’s to seek a builder, or in clearer terms, shift from the kind of reflective contemplation philosophy provides, to developing a more active capacity to eventually participate in the living activity that enacts philosophy. That living activity of Spirit which labors, sacrifices, and loves that blueprint into existence is what we seek. Fundamentally, this is what I think is clarified by the Steinerian turn. From the closed circle of thought thinking itself, to the open development of capacities that allows consciousness to interface with the beings who think the world into being. This marks the passage from the philosophy of the Concept, to the science of the Spirit that utters it.

Steinerian turn…

The “Steinerian turn”, so to say, is deeply informed by Goethe’s revolutionary method, which exchanges the spectator stance or pseudo-Archimedean point of thinkers like Darwin, for an active, imaginative “slipping into” organisms, or beings. Where Hegel’s retrospective method can only logically reconstruct the concept of life, Goethe’s practice of inwardly tracing the metamorphic gestures of a plant in Metamorphosis of Plants8, and so experiencing a formal law of expansion and contraction, begins to reunite the knower with a generative force (the generative force of that particular being), which is in actuality the generative force. Steiner radicalized this into a conscious spiritual science, where through disciplined inner activity, the observer transcends representational thinking to experience, not just in deducing, the spiritual reality actively shaping the phenomenal world. There is much to be said about the moment of recursion that Steiner pioneers in Goethe’s approach. Nevertheless, for now, I will refer only back to the section on the importance of recursion in a system of totality. Steiner’s continuation of Goethe here fulfills the imperative to move from Hegel’s perfect “map” as Concept, to the living territory of creative Spirit.

There is an unacknowledged reader tagging along this blog post: the committed Hegelian. After me “totally obliterating Hegel” and proving he’s crazy and nonsensical and such, I would like to preview a few responses I’ve received from Hegelians, and where they go wrong. The dynamic between us, as interlocutors, is defined by a conflict of totalities. The “Hegelian”, let’s say, is claiming totality, just as the “Steinerian” (or any person whose system accurately captures the “beyond” of Hegel’s system) is. The situation is quite similar to the very beginning of this article, where claims to the totality of the object are made. Practically we can demonstrate the result: when confronted with a being, a spiritual being, such as an Angel, the Hegelian will interpret it as a Vorstellung (representation) that must be subordinated by the Concept. From this vantage, the Steinerian appears to be stuck in picture-thinking, mistaking an immediate mystical representation for true ideality, which for Hegel resides solely in the mediated movement of the Concept itself. After all, the true mysticism, claims Hegel, is in speculative thinking. Mysticism for him is a product of the Understanding. This isn’t a dismissal of the Steinerian, if I were to steel man this position. It is a correction, it is counsel to go further and meet the Concept. This is a profound reduction of the Steinerian standpoint. When the Steinerian says the Angel is Idea, the Idea is meant in the same sense as Hegel, but as something more concrete than Hegel’s Conceptual Idea. It refers to active, intelligent beings who are architects of spiritual realities and can be perceived beyond ordinary sense-experience. The conflict is surely amplified by a shared vocabulary that masks divergent realities. Here is another example: When Beinsa Douno writes that he spoke to the Slavic folk-spirit, the Hegelian comprehends this as a conceptual grasp of historical and logical necessity, such that a concrete figure (man) represents the soul of the Slavic people. The Steinerian says: no, he talked with an actual person, a spiritual person. He engaged in a participatory acquaintance with a conscious, guiding intelligence that was not a human. One of these standpoints is a knowledge about, reducing the thing to a representative of the thing (which is quite Kantian), and the other is knowledge of the thing-in-itself directly, by acquaintance. The highest practical example (that is to say, an example in practice) can be found by reading what Hegel says about the plant and what is logically entailed by it. Once this is finished, the Metamorphosis of Plants by Goethe provides a stunning parallel (although it is not entirely correspondent to Steiner’s project, it is in the same Spirit of what a project of post-Hegelian totality looks like). In one text, a kind of categorization is going on, and in the other, the subject is fully participating in the being of the object.

An issue being faced thus far is on language. Shared languages creates an illusion of common object, suggesting either a need for proprietary terms to dispel this conflation, or perhaps the strategic use of Hegel’s own language to reveal where his system points faithfully beyond itself. As of now, I am currently leaning towards the latter. This impasse resembles the reactions to the Ontological Argument. One either grasps it as a self-evident truism, or misunderstands and places that misunderstanding on part of the OA itself. The limit is not logical, but of the possibility of the subject’s being itself, and so it suggests to me that the ultimate resolution might not be argumentative, but transformative. Requiring a direct spiritual encounter- be it with an angel or Christ or by being instigated by psychadelics- that irrevocably shatters Hegelian Orthodoxy in a way that it cannot conceptually absorb. When put that way, it sounds almost threatening, that the solution is forced initiation, because that is what initiation is, a staged or controlled revelation.

The map is complete, with the relation between the map and the territory being that the map is the territory’s logically concluded past. A new domain is necessary to enter this territory as an ongoing creative future. Anthroposophy (Steiner’s system) seeks to enter this territory with the subject as an active collaborator within the Absolute. In light of this, allow me to borrow a metaphor from the earliest part of this article. The great anatomist of frameworks, Northrop Frye, sought a method for immanent genesis, one derived from the total structure of literature, and achieved it. By the same token, Hegel achieved this reality for itself, having sought an immanent genesis of the totality of totalities. Truly, there is no better comparison. Hegel himself is the ultimate critic, having given an immanent criticism of all there can be criticized. His system is the complete and perfect review of the “cosmic text”. Consider a work of immense complexity. A tapestry of history and references. The masterful critic can unveil its architecture. Perhaps he or she can explain how this or that detail relates to the whole, or how the prose supports the ethos of such and such part. The critical act is one of profound recovery and understanding. Yet for all its brilliance, the hermeneutic remains retrospective. The critic can reconstruct the logic of the fall of man in the Bible, but the critic did not cause the plummet. The critic can explain the symbol, but is not enduring the lived reality from which it exists, such that it is conveyed in the form firstly encountered in the text. The genius of criticism is to comprehend a world already made, not in making the world anew, nor in creation in general. Steiner’s project, therefore, is not to be a better critic, but to become a potential author, and train you to become one as well. The change lies in the move from perfecting interpretation to developing the faculties to participate in the “writing” (as a matter of metaphor, of course). Enough has been done to analyze the divine logic, but not enough has been done to collaborate with the divine author.

In laying out the nature of truth, being, and the general arc of my narrative, there are bound to be accusations levied at me from a Hegelian flavoring. The first is a common one. It asserts that Steiner’s quest for real-time, participatory knowledge fails to grasp that retrospective comprehension is not a philosophical limitation, but the very form in which Truth actualizes itself, and that what he calls a “higher” activity is already the immanent, self-unfolding work of Concept. This is correct, however what is not grasped is that anthroposophy, as explained above, addresses a different activity altogether. Steiner fully acknowledges that retrospection is the mode of philosophical comprehension. His critique is that this mode is passive in relation to the creative act. The Concept’s “self-unfolding work” in this case is logically reconstructed after the fact by the philosopher. There is a necessary addition found in the capacity to co-participate in the unfolding as it occurs, such that Concept is not actually constitutive of that self-unfolding work. In other words, retrospective comprehension is the form of Truth-as-Known, but anthroposophy aims at Truth-as-Lived-Creation. The former is certainly necessary, but insufficient for the consciousness that seeks not just to understand Spirit, but to work with and within it.

Sidenote: It is almost inevitable that the philosophically minded (meant as an insult) will hear the words “reflection” or “reflective act” and construct a straw man to attack as if I am operating with the premature logic of Essence that Hegel dispenses with by the time the system develops to the Concept. The individual capable of laying out the whole path of Hegel’s philosophy; one capable of understanding the distinction between Essence and Concept, is surely someone with enough expertise to not make such a blunder in thought. Certainly I am no expert, but absolutely not a novice. It reminds me of that one tweet that goes, “Little Caesars tastes so good when you don’t have a b—- in your ear telling you it’s nasty”, only it’s to the tune of “Talking with people feels so good when you don’t have people intentionally misinterpreting you”.

Another accusation is in the same form as the previous, that the thinker is somehow misguided and not accounting for how the Concept already subsumes what one is saying. “Is Steiner not simply mistaking the acquisition of new perceptual content (or spiritual data) for the development of an entirely new faculty, when from a Hegelian standpoint any new immediacy is merely fresh material for the one sovereign faculty of thinking and Reason to mediate and comprehend”? This may sound devastating, and it is. For the Hegelian. For the Steinerian, the claim that “any new material is fresh material for thinking” proves his or her point! It confines all experience within the form of reflective thought. Steiner insists that spiritual perception is not just new content, but a qualitatively different relationship to reality, where the perceiver does not stand over and against an object, but consciously lives within the being of that object. The faculty is new because it overcomes the subject-object distinction inherent in sense-perception and logical reflection (and if the position is held that Hegel also overcomes the subject-object divide in philosophy, then at least it overcomes it in a way previously not standardized before). It is a participatory knowing, not an observational thinking. To call this “new material” is to reduce an active to a passive.